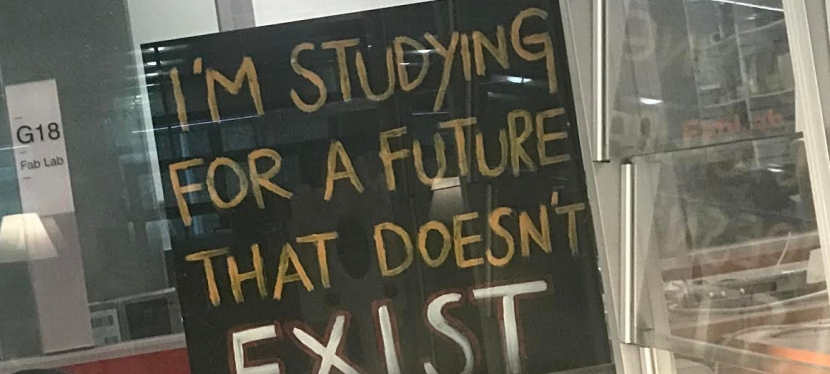

I walked past the above placard the other day at my architecture school and thought; yes, that is pretty spot on. But regardless of the climate emergency, it also made me think about architectural career paths.

There are several theories advanced about architectural career paths. The traditional career path is arguably no longer sustainable. Given the lack of industry research into career trajectories of people who have graduated as architects, the alternatives and different pathways are murky, and I suspect no-one really knows what is going in.

Blah-blah-blah

After my second post-graduate degree (my first was in urban design), I was never going back to architecture. After five years or so years of practice in the Keating years, I was over it. Sure. We could have kept going but it wasn’t just that the remuneration was too low it was the fact that the other incentives and potential rewards were also few and far between.

At that point, I even struggled to get a sessional teaching job at my old architecture school. You might ask why not? (and I am sure some of you older colleagues reading this have extremely selective memories or have chosen to forget). My truth to power antics never really went down that well. It’s probably career-limiting to call out soft corruption and the inequities of provincial star-lord favouritism. Even worse to get a few petitions going.

In any case, it was awesome to get out of the small architecture bubble I had existed in for almost twenty years. Some of my esteemed peers are still in it and have never really left it. A few have even had more predictable career paths. But, I weep for them. In contrast, my career path has been more exciting, chaotic and haphazard (I love my job). But, there was no way I was ever going to ‘selected’ to be an associate or tracked to be a principal in a big practice.

So what are the options for those who graduate from architecture schools in Australia?

Graduate, get registered and then go into practice.

One question: Why would you do it? Your design education probably hasn’t equipped you for business. Apart from a grab-bag of graphic skills it perhaps hasn’t provided you for branding, marketing, networking and sales—yes let’s be blunt, and use the word sales, because that’s what it is. It will probably take you maybe ten years to have sustainable cash flow business. This time might be quicker if you are smart and good at strategy, leadership, negotiations and operational tactics. The time might be faster still if you start with more than three people.

Of course, if you want any life balance, want to have children or afford a mortgage, then it’s a tough gig. Architectural practice is about the hardest thing you will ever do, and no-one will reward you for it.

Graduate, get registered and work in a sizeable self-sustaining office.

This may be a good option. Providing you don’t get typecast or stereotyped as the BIM guy or the interiors girl, model-maker or the office hipster barista. Ask if your office has a graduate program or leadership mentoring or focused in-house CPD. What about a design mentoring program for those hotshots who think they can Pinterest design as soon as they graduate.

Contract to Contract.

If you love hanging out with recruiters and like being a kind of lone wolf expert, this might be ok. But contract work, including the expatriate kind, relies on a strong national or global economy. To do it, you will need enough experience to convince a recruiter that you have some kind of special knowledge of expertise.

Something else.

Yes, not everyone who graduates from an architecture school wants to be an architect. But architects are trained in a unique way of thinking that no other discipline has. Architects can make great CEO’s general managers and policy leaders. Architects generally make better than average politicians.

The chilled options: beats, beans, beards craft beer, or furniture making.

A variation of the above point.

Adding on some ancillary qualifications

I know lots of great people who have gone into Project Management. But maybe we should encourage more of this. But hey, don’t we architects hate project managers? Add on another related degree like property or construction management or landscape architecture is probably a good idea. An architect with a follow on Quantity Surveying degree? Now, that would really do my head in.

The Academia option

The less said about this option, the better. Let’s say it’s a pathway akin to getting a camel through the eye of a needle.

The start-up option.

One of my favourite options. Start your own non-architectural biz, or perhaps slightly related, business from scratch. But you will need lots of help and mentoring from others to do this because what you learnt in architecture school has probably not fully prepared you for the wonderful world of start-ups.

Climate emergency activist

Yes !!!! We should all be this and call out the green-washers and business as usual types.

Architecture is at a tipping point. Is it still a viable career?

As with recruiting procedures, the career development processes and infrastructure in architectural firms are, for the most part, pretty crap. If the Australian Institute of Architects were serious about industry reform and advancing the cause of architecture, it would get rid of the awards system.

This move would force individual firms to get serious about their branding and marketing, break the stranglehold of the star architects and save a whole lot of money on those futile award entries.

Yes, to reiterate, one of the best things the Australian Institute of Architects could do if it were serious about inclusivity would be to scrap the awards system entirely. Wouldn’t that be a hoot?

The award system only perpetuates the existing ecologies of privilege, mythologies and stereotypes that have been so damaging to the architectural industry. Developing the careers of young architects once they graduate should be a priority for the whole profession. Instead of spending all that money on futile award’s submissions, architects could spend it on the most critical thing in their offices: The talent.