In keeping with the theme of #Freespace, the Holy See has commissioned a number of small chapels on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore for the Architecture Biennale. There are 10 chapels in all. The commissioner was His Eminence Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi. For whatever it is worth Cardinal Ravasi is the president of the Pontifical Council for Culture. Isola di San Giorgio Maggiore is the site of the chapels and the place where the Benedictines first inhabited Venice in the 10th century.

The curators were Francesco Dal Co and Micol Forti. The curators asked the invited architects to consider the chapel as a place of:

“orientation, encounter; meditation, inside a vast forest seen as the physical suggestion of the labyrinthine progress of life and the wandering of humankind in the world.”

Magnani and Traudy Pelzel were the architects of the introductory pavilion, where the exhibition starts with a kind of small chapel dedicated to Asplund’s Woodland Chapel of 1920 located in the cemetery of Stockholm. A suitable introduction to the architectural explorations of the 10 chapels.

The invited architects were Andrew Berman, Francesco Cellini, Javier Corvalàn, Eva Prats and Ricardo Flores, Norman Foster, Teronobu Fujimori, Carla Juacaba, Smiljan Radic, Eduardo Souto de Moura, and the Australian architect Sean Godsell.

I never thought I would say it, but Sean Godsell’s chapel is an exceptional contribution to this endeavour. Let me repeat that. Indeed, I never thought I would write these word’s, but the small chapel designed by Sean Godsell is tremendous and certainly better in many respects than the chapels by the other architects.

Catholic liturgy

The Godsell chapel does not seem to just recreate what one might expect of some of the auteur architects represented here. What’s more, it seems to speak to an understanding of the Catholic liturgy that is not merely superficial, thematic or the usual riffs about sunlight, the sky and the meditative life.

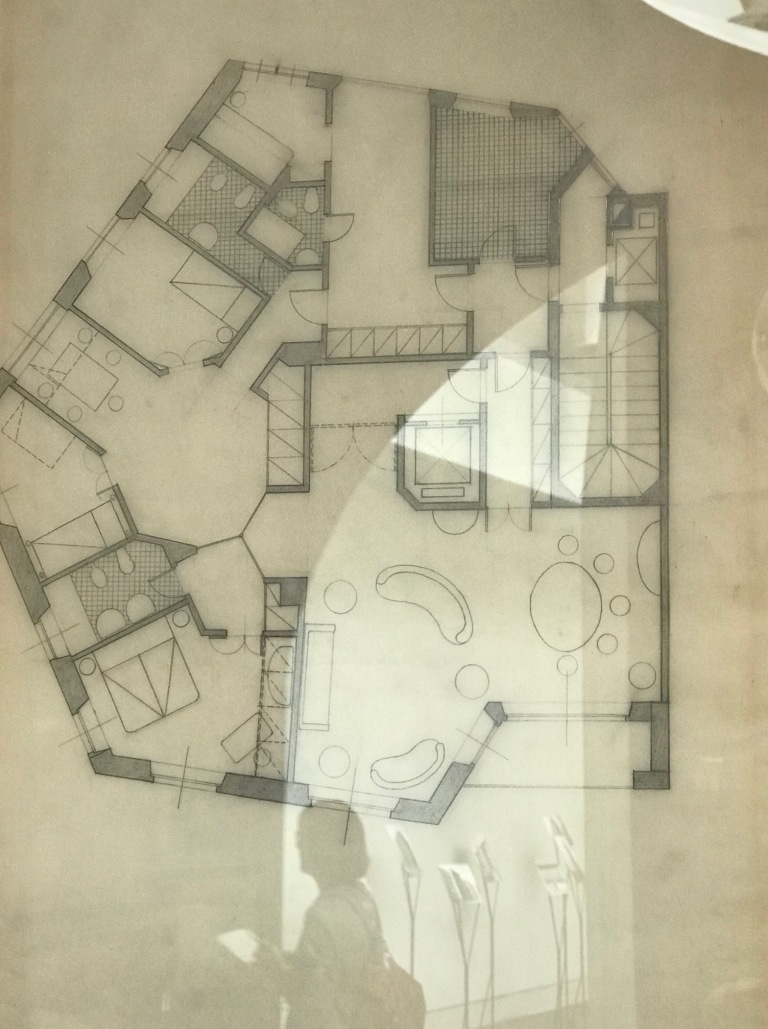

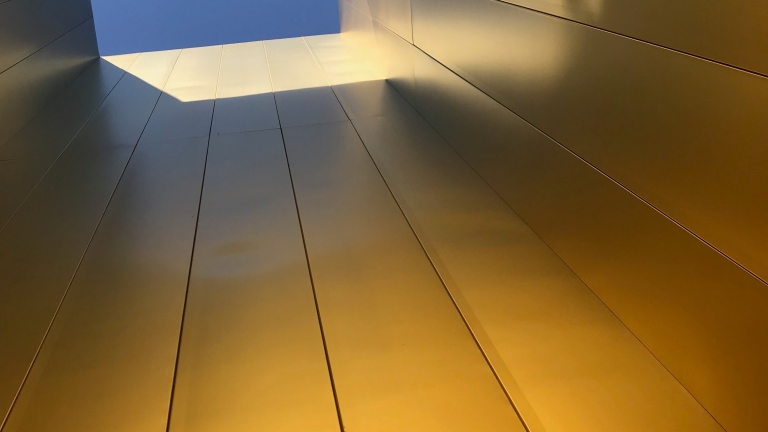

The Godsell project’s strength is that it is a discernible celebration of the Catholic liturgy itself. A celebration of its gestures, and a celebration that intimates that once its panels are closed, they could then be re-opened. The laity seating is distant from the altar, and the altar itself is all hot-blooded galvanised steel; above which is a gold metallic light shaft, even the hydraulic canisters, which support the verandah like panels, seem to suggest that this is not a static place but a working and operating chapel. The hex screws look like they have been drilled in so hard they are stigmata. The small primitive half-log benches for the laity are outside of the main area but these face the altar. The message is clear: the priest-architect is at the centre of this chapel.

The galvanised steel work reinforces a sense of temporality in the way that appears to imply the chapel can be opened and closed. It would be interesting to see how the light on this chapel changes with the season of the Venetian lagoon. One could certainly imagine rituals, Catholic or otherwise, taking place here. It is orientated to both the sky and the lagoon, as well as a focus that directs worship towards the central liturgy of Catholicism.

The BBQ and the Design Hub

I have heard a few of the other blokes sniggering to say that altar looks like a BBQ, in the summer heat of Venice its natural to think you could easily fry a few strips of kanga on it. I am not sure how our collective critical faculties came to such blithe readings. Its always easy to scoff at the architect-priest driven by intuition, who readily conforms to the trope of the holy monster or outsider architect. But hey whats wrong with the barbie. Isn’t that what the Catholic liturgy is all about in a way: red meat, eggs and poking forks into flesh. Every Ozzie, Ozzie, Ozzie, Oi, Oi, Oi, BBQ is a kind of transubstantiation in its own way.

Now I am being blithe, but more seriously, this project in Venice suggests that a reading of Godsell’s largest project to date, the Design Hub, could be seen differently; a jewel box or casket, a kind of crematoria and chapel situated in a profane world. Arguably, the pragmatic controversies surrounding the Design Hub have distorted a critical reading of it and the architect’s intentions. No matter how much that intention might be the result of an intuitive and primal sensibility adrift from theory.

Christ Almighty

Can we just write off such architectural contributions as ecclesiastical outliers for the faithful? Or can we scoff at them in with all the instruments of secular rhetoric? Does religiosity, whatever form it might take, really matter and is its representation in architecture anything we need consider? Interestingly, the Melbourne School of architecture (let’s call it that for the sake of simplicity) has been driven by a big swathe of Christological narratives. By focusing and drawing attention to the actions of the ritual itself Sean Godsell’s approach is different to the embedded symbolic narratives of Howard Raggat’s designs for our city and probably more straightforward than Peter Corrigan’s work and the complexities of his theatrical catholicism. What is interesting is a big swathe of our city, and the tribal life of its architects, has its origins and legacies in the work of these very Christian architects.

Catalan Pavilion

A useful comparison to the Holy See’s contribution at Venice is the Catalan Pavilion. This pavilion is suitably distant from the main centres of biennale action. Of course, given the politics of Catalonia, it appears telling that the Catalan architects RCR, recent winners of the Pritzker prize, would be on the margins of the Venetian lagoon. Approaching the Catalonian exhibition you find a tin shed; another temporary fragment built on all the other fragments and accretions that have made Venice. But unlike many of the other National Pavilions of this year’s Biennale, including the Australian pavilion, this exhibit presents a dream sequence of images rather than some polemical rhetoric about architectural nationhood. As the architects themselves say:

“Architecture shouldn’t be about doing difficult projects and iconic buildings but about creating spaces in which people can have their own experiences and develop their own creativity,”

The Catalan pavilion “Dream and Nature,” evokes the landscapes of Catalonia and the relationship of the architects to this place.

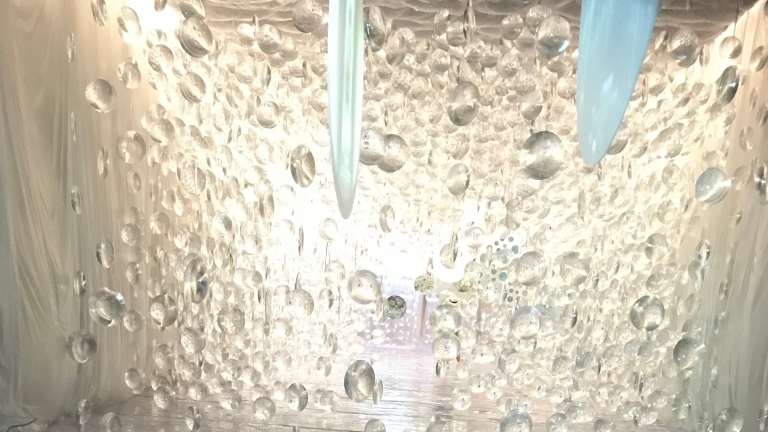

Filled with glittering plastic lenses, grainy media projections and whimsical images of nature the Catalan pavilion presents a series of unstable images that seem to exist between waking and dreaming. If one of the primary tasks of modern architecture is estrangement, to make us perceive things differently, then this pavilion achieves this. (Shklovsky’s literary notion of defamiliarisation and estrangement and its relation to the forms of a tradition have always seemed fitting theory in this regard).

RCR’s Catalan pavilion, called “Dream and Nature,” takes the visitor far away from Venice’s canals by evoking the woodlands, fields and volcanic hills of Catalonia. The pavilion presents images of 120 hectares of land in Catalonia that the three architects bought and have started to turn into what Mr Aranda called “our legacy” — a farming property that they aim to make a place of study and reflection about architecture and how it interacts with nature and with other disciplines.

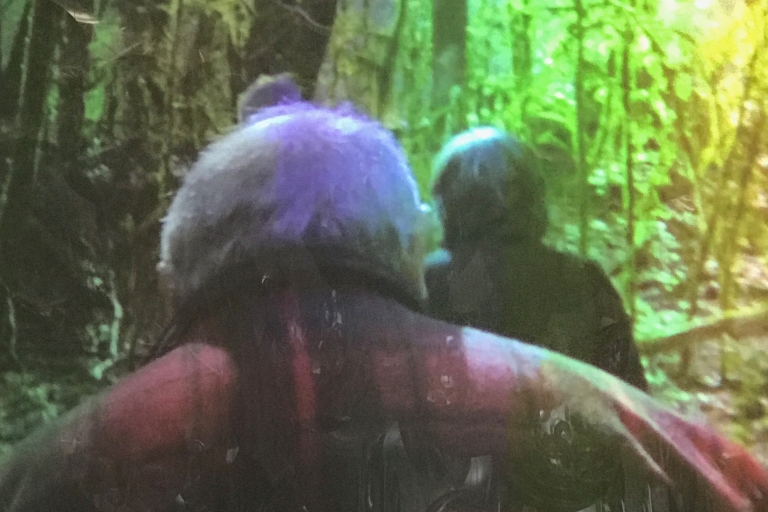

There was a moment in the Catalan pavilion, projected onto one of the lenses, where the architects are walking through a forest. It is like they had abandoned architecture and had become children at play, positioning architecture between nature, folklore and the spirit creatures of their own land. That’s the kind of kool-aid I want to drink.

The Burbs

As for the spirit creatures in our suburbs. They have all been killed. Killed by the big roofed Christian churches, Ronchamp look-a-likes and basic brick sheds next to the suburban freeways. Yet, both Corbusier’s Ronchamp and Asplund’s chapel advance an architectural language based on a ancient animism celebrating a primitivist and folkloric nature. A natural and organic world separated from the strictures of organised religion. For modernists and those who succeed them religious buildings have perhaps always presented a dilemma. What are the appropriate modes of representation and architectural language for such buildings? How do Architects build programs that represent different faith communities? The efforts in Australia to build mosques that counter Muslim racism indicate other examples of this genre. Moreover, how do we build on country?

Nowadays every city has its own little-bejewelled icons. Little nuggets and follies designed to travel through our social media feeds with dreamless iconicity. Image canoes determined not to dissolve or get swamped or sunk or lost on Insta or Twitter. Canoes attached to confected outrage or bland boosterism.

What is the point of follies, or exhibitions if they do not estrange our minds, or take us to past rituals and lost dreams. So what can we say about sacred liturgies, pagan rituals, dreams and wanderings at a time where every city has its follies and pavilions. Have we become slaves to a political economy of iconicity that is really not making our settlements any more living or sustainable or resilient or smart?