There was a time when I was right into suing new technologies to do things. I was enamoured with various techniques of reprographics and representation. I was right into all of the architectural making machines of the late 80s. I loved the bromide machine, the dyeline (I loved the smell of the ammonia), Pantone paper, reverse bromides and of course that greatest of all devices the PHOTOCOPIER.

Of course, I had no illusions about using these technologies to save the world. It didn’t need saving then, but it did need fucking up. At that time, in my tiny architectural brain, the principal means to achieve this was through the critical commentary enabled by collage. As a result, my modus operandi was the comic. And it was always fun to see the grand poo-poo-bah of my architecture school totally flip whenever he saw my seemingly insane comics.

Nowadays, all of the old reprographic techniques that I had some expertise in have disappeared. Even the long studio nights in dimly lit rooms where we suffered under the light of oh so long architectural slide shows have gone.

All of the above has been replaced with graphical interfaces, Kuka robots, 3D printers and non-existent supply chain drones. For some, these new technologies will save us from climate catastrophe. Why will these things save us? Because, apparently through these technologies and processes, we are going to save the world by producing less waste and emitting less carbon. Sadly, I don’t believe that.

However, if you believe in simple fixes and bad architectural science, and you want to get onto the parametric revolutionary bandwagon, then jump on board; and you might then enjoy the ride with all of its naïvety, good intentions and the curious know-all vanity that goes with those intentions. So, what follows is all you need to do to be a Parametric revolutionary.

1. Talk about revolution

Yep, that’s right the revolution is going to happen. It’s a technological revolution and its coming tomorrow. And all you have to do to partake in it is to learn how to code and make stuff. You don’t have to think about revolutionary politics or even think about the sophisticated software development cycles of the tech giants. Nup, all you have to say is that a ‘revolution’ is on its way. Even better put another word in front of the word revolution.

2. Talk about the planet.

Yep, talk about the planet as if it’s something you can fix and engineer with some new really cool technologies. Geo-engineering maybe? Floating cities? Beautiful little orange tables and nick-nacks made with robots and ‘new’ materials?

3. Use some fabulous words.

Here are a few: prototypical, performative, materiality, speculative, trajectory, distributed, integrated, deployment, customised, networks, generative, elasticity, composite, non-linearity and of course the word that makes me think of an abattoir’s conveyor belt: machinic.

Wow, that word, ‘machinic’, really sums it up. Its diction is so precise when it comes out of the mouth in speech. It sounds like its got a bit of philosophy behind it ( Deleuze and Guattari) and it implies an ability to control things. To control elements in an objective, rational and seemingly engineered way, to control shit that might otherwise get out of control.

4. Chuck in some systems theory.

Yes, mention the word systems a lot as it will give the impression that a wholistic, organic and multi-layered approach is being pursued. Add the word systems after other words. For example, ‘Foam systems’ is one thing I read recently. But hey, what was actually meant by this was making stuff with polyethylene styrofoam.

But all the systems theory in the world doesn’t help us untangle the complexities of our current modes of carbon production and rampant carbon emissions. Just saying the word systems doesn’t account for a complex understanding of ecological science or a dismantling of anthropocentrism.

In the 1920s, even Bertalannfy, the founder of General Systems Theory, was to contrast the mechanistic, or machinic, approach to biological disciplines and he consequently advocated:

‘an organismic conception in biology which emphasises consideration for the organism as a whole or system, and sees the main objective of biological sciences in the discovery of the principles of organisation at its various levels.’

5. Sustainable

How many times have we heard that word? Don’t you love it? As a word, sustainable has certainly been misused.

But for the Parametric Revolutionaries, it can be used to make it all seem ok. It doesn’t matter that all of this technology and verbiage is half-arsed because it is ‘sustainable’

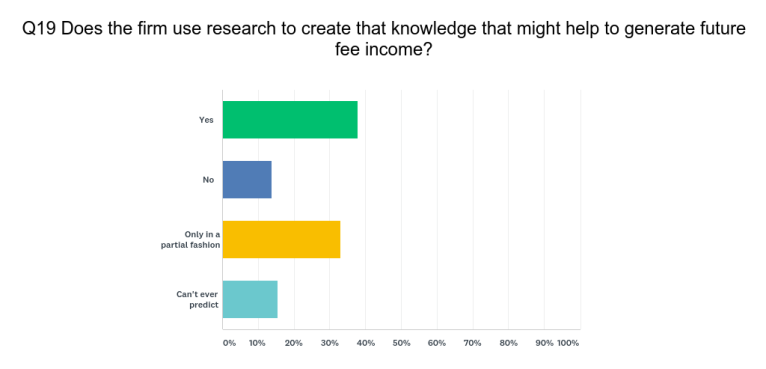

6. Argue for the holiness of BIM.

Invoke the sacred name of BIM. But ignore its dreary and banal impact on our suburbs and cities.

Our suburbs are becoming multi-residential BIM libraries. We all know the look. It’s a charcoal grey orthogonally articulated off-site concrete panel kind of architecture. Streets jammed with buildings with lots of frames and framing, volumetric blocks, rectangular slit windows, little black steel window reveals and striated timber slats on steel frames that you know are going to fall apart in a year and glazed balconies you could vape on.

7. Stop talking about architects as architects.

So old hat to even call ourselves architects. Lest call architects: building engineers, design technologists or better still superusers.

8. Be Male

Yes, much harder to be a Parametric Revolutionary if your female or non-binary. The parametric revolution is a predominantly male discourse and hey where would we be without all those Zuckerberg dudes in the Silicon Valley incubators.

As I write in my forthcoming book, in the back office of every Warlord or star architect, there is the ‘BIM guy.’ Who is more often than not rubbing shoulders and linked to the other guys making the new generation of AI armaments.

Parametricism is like Pornography

The entire Parametric discourse the obsession with revolutionary fever, the big dick geo-solutions, the spitting diction of parametric words, the fleshy appeals to organic systems, the feigned softness of sustainability, the eroticism of BIM, the fetishised names and power of remotely operated drones all evoke the technologies, genres, scenes, scripts, words and objectification that we might find in pornography.

There are too many parallels. But that’s ok because all of the new materials and technologies are just around the corner and it’s all going to be ok. When the planet warms by two or maybe three or even four degrees, the Parametric Revolutionaries can hose it down with parametric spunk and that will save us from extinction.