My local branch of the AIA had its awards jury presentations last weekend. I wanted to go and have a look at few categories. Sadly, an impending conference paper deadline prevented me from attending. I might go to the awards ceremony I am hoping they will get out the red carpet this year and then there might be a few protests like the one above at the Baftas.

But like all good awards punters I had a look at the form guide. It was ok as far as lists of architecture go. As someone reminded me during the week the culture of architectural practice in my city is vibrant and well developed with its own legacies, tribal distinctions and pecking orders. The stability of this pecking order never fails to amaze/annoy me. I remember when I went to the awards presentations one year after a significant absence and felt like I was returning to my old high school. I wondered, what has really changed in 20 years since I left architecture school. Same principal, same deputy principal, same prefects and house captain’s same acolytes and lackeys. Same old, same old, so called “rebels” and other people on the outer. Which was actually just about everyone else who wasn’t in the principals group. Everyone in their place, certainly not a lot of difference and inclusion, as Roy Grounds was reputed to say: “Melbourne is a rich smug city.” There is a downside to existing in a city with a strong practice culture.

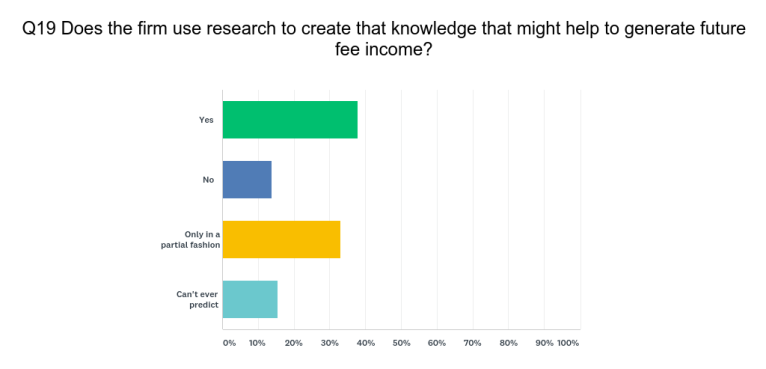

I love this chart by Deb Verhoven mapping the awards in the Australian film industry. I am sure this the same in the architecture awards networks.

Even so despite my misgivings and raw cynicism, even though I couldn’t go to the presentations this year I had a look through the categories there is really a lot of very impressive architecture in each category. The small category for small and micro projects was a stand out.

Anyway the categories for the Australian National and Victorian awards go like this and both have pretty much the same structure: Public Architecture, Educational Architecture Residential Architecture – Houses (New), Residential Architecture – Houses (Alterations & Additions), Residential Architecture – Multiple Housing, Commercial Architecture, Heritage, Urban Design, Small Project Architecture, Sustainable Architecture, Enduring Architecture (What is this exactly?), International Architecture And of course that great anti Trump Tariff award: Category A1: Colorbond® Award for Steel Architecture.

Yada, Yada, Yada.

Raisbeck’s Form Guide

So after checking out the categories I set up my Ladbrokes account app on my phone, where you can bet on the wards, and decided to put my money on the following in the Victorian Architects for the Awards. So here is my quick guide to the firm.

In Small I like Brickface Austin Maynard Residential its kooky and small should be kooky. I am sucker for the cute brickwork.

In Residential Alts and Additions I like Templeton Architecture’s Merriwee. Those bricks are fantastic. So Yassss !! maybe I am a real sucker for the brickwork If architects cant do great brickwork who can? I wouldnt give any of my awards to Rob Mills because everytime I open the internet I am delivered a targeted ad for this firm. Mills should check his advertising algorithms.

In New Housing: Compound House, (although I like the Panopticon but maybe it’s just the name and the Foucault reference). In Public Architecture: I like the cop shop for Melbourne’s most disadvantaged outer suburb.

In education I was worried this category was going to be full of middle brow aluminium external panelled with sanitised teaching spaces. But I was relieved to see 18 Innovation Walk Revitalisation Project by Kosloff Architecture, Callum Morton and MAP (Monash Art Projects). Maybe these guys don’t deserve it because they have been such baddasses with form, but hey why not. In multi residential my pick is: Nightingale 1 by Breathe Architecture It would be criminal if this did not get the award. There rest of the category is train wreck that deserves a dissertation on it own about the corrupting influence of developers on architects.

So after placing a few bets, I am thinking all of these award categories don’t really do architects justice. There awards system in this country is too object focused. It’s remarkable that for the professional bodies to devote so much of their marketing efforts on the awards for architect design buildings.

Even Architeam has an award for unbuilt projects and an award entitled contribution. I think that is great idea. I was judge for them in 2013 and they never asked me back. They have a slightly different system to the other professional body. One jury to judge all the categories. That can be ok. The year I did it here were 3 or 4 of us. Last year there were seven on the jury and of course, it is said that, the egos came out and the project I was involved with as a client, I think, was shafted. I think the let’s be precious and not give out too many award’s brigade held sway. Architects need to give out more awards rather than less.

More is More and not Less

So it goes without saying architects need broader categories of awards if we are to successfully market the profession in the new millennia. So it would be great to give out awards each year for contributions to research, architectural education, public advocacy (the anti-Apple crew), or one for sustainable advocacy, or design leadership and of course business leadership, or maybe just leadership in the profession. How about an award for Parlour ? Or an award for architectural media? Or an award to someone who has done a lot to promote Melbourne Architecture to the world ( I am thinking of you know who)? By this strategy you might even get some people from outside of the profession of architecture to participate in the judging.

Or maybe, you could also do critical negative awards. I am thinking best hot-shot firm from overseas who gets the commission, fees, publicity and then leaves town. Leaving the town looking, and living with a dog of a public building (will this be Apple?). In parochial parlance this award could be called the Wombat award. Or maybe, a Weinstein like award for the best octopus like local star architect or director and then you can have awards for the most exploited student, or recent graduate, or most underpaid mid-career female architect. I won’t go on.

Is the profession so moribund and stuck in its parochial awards culture that it can’t get out of the rut of only thinking about buildings? There are a lot of architect’s out there who aren’t architect’s in the narrow and traditional sense and their contributions should be recognised. Plus, we need to recognise both architects and firms at all stages of their careers.

Maybe if we had more categories and more vision, I would stop thinking, in my more cynical moments, that the awards systems is just replicating a favoured circle and narrow canon of bourgeois, liveable and sustainable slop and that only the chosen few will ever get the prizes for.

The featured image above was taken by Hannah Mckay of Reuters.