‘Building Information Modeling (BIM) is a digital representation of physical and functional characteristics of facility. A BIM is a shared knowledge resource for information about a facility forming a reliable basis for decisions during its life-cycle; defined as existing from earliest conception to demolition.

To mandate or not to mandate that is the question for policy makers. In the UK a BIM mandate was announced in 2011. The purpose of the mandate was to aim to get “all collaborative 3D BIM (with all project and asset information, documentation and data being electronic) on its projects by 2016.” There are various opinions about this type of approach and whether or not it is effective. In Australia no such mandate exists and public procurement policy in the construction sector is largely left to the market and a few haphazard initiatives by state and federal government. Almost every state has a different take on procurement decisions and policy. But in the UK the BIM mandate policy has driven research examining BIM implementation and its impact on the sector. It goes without saying that this kind of research (research into BIM and digital workflows in Construction) is much more advanced in the UK than it is in the Australia.

For architects and others, a primary problem in formulating research and innovation policies around digital workflows and procurement is the spin that surrounds BIM. It is easy to feel swamped by all of the universal claims made about BIM. Rather than thinking how great BIM is we should ask: How can we manage and develop the capabilities of the majority of small practices who hope to engage with BIM?

My concern is threefold: that BIM is only for large practices, BIM contains and limits the architectural design process and that BIM is a means by which architectural knowledge is made redundant in the name of economic efficiency. I know it sounds paranoid but will BIM engineers and technicians replace architects?

I know of a few small practices that have purchased BIM licences only to then not get time to implement it. Apart from having the staff to use these systems effectively there is the issue of setting up a system to manage the data, information and knowledge that such a way of working requires. A Great journal paper on BIM implementation within the firm is from my colleague Dominik Holzer. Whilst written a few years ago it has some good hints on the problems of BIM implementation. His discussion of the Macleamy curve is well worth the read. His BIM managers handbook is great.

Myth 1: BIM change will change everything.

The first problem with BIM is that it has been linked to everything. A kind of all encompassing saviour. For some of its proponents it is a kind of panacea for everything. In theory, BIM project models paired with collaboration tools offer a number of significant improvements and benefits over traditional design, delivery and supply chain processes. Proponents of BIM claim that the BIM will change everything. In current BIM research BIM is linked to Lean Construction, Augmented Reality (AR), project and trade scheduling, safety management, progress measurement on sites, design visualisation and is even seen as a saviour of architectural education.

The BIM literature is full of these kinds of universal claims and possible linkages. Call me cynical but I think its pretty easy to get on a technology bandwagon these days.

Myth 2: BIM is the most important and singular mode of digital representation.

Definitions of BIM already have notions of digital representation built into them. For example, the building SMART alliance (Building Smart Alliance 2012) definition of BIM as:

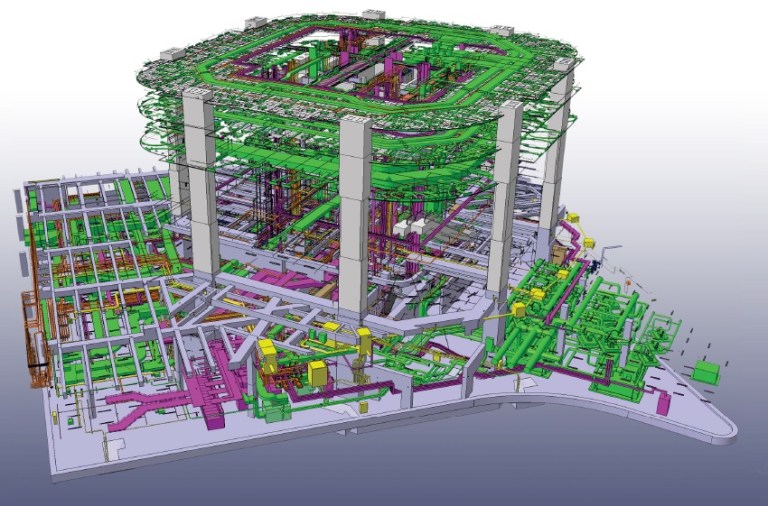

‘Building Information Modeling (BIM) is a digital representation of physical and functional characteristics of facility. A BIM is a shared knowledge resource for information about a facility forming a reliable basis for decisions during its life-cycle; defined as existing from earliest conception to demolition. A basic premise of BIM is collaboration by different stakeholders at different phases of the life cycle of a facility to insert, extract, update or modify information in the BIM to support and reflect the roles of that stakeholder’.

The danger with these all encompassing definitions, especially given the other claims made about BIM, is that it might easily be seen, and come to be seen as, the only means to represent buildings digitally. This is a tendency that I have to fight time and time again teaching in the design studio. Sometimes architecture students think the computer is the only one way to do things. Yet, there is a whole range of modes of representation at the architects disposal: From physical drawing to model making to a full range of software applications. But all too often I get students who think that the computer model is everything and there is no point building different models or testing designs in any other way.

Myth 3: BIM will replace drawing.

Iterative hand drawing or sketching is central to design practice. But, Ambrose (2013) for example claims that BIM represents a new mode of visualisation that will overwhelm traditional conventions and working tools of abstract design thinking such as the “traditional conventions of communication; plan, section, elevation,” In this view BIM is a radically new tool for abstract design thought because of its “ability to virtually simulate the building construction and architectural assemblage” and “is perhaps the most important transformation and architectural production in the last several hundred years.” Proclaiming that “Every other discipline that has adapted simulation as its primary model of design and fabrication has benefited from increased efficiency and economy. Simulation is the destination of contemporary digital design.” It’s shocking that someone would actually write the above.

Like Ambrose (2013) the lean construction proponents Koskela and Dave (2013) also argue that BIM visualisation is superior and that “Traditional design methods do not support sophisticated and accurate visualisation or rapid iteration and evaluation of ideas that will help clients decide the option(s) to select.” Invoking parametric design and seeming to limit and lock in strategic or conceptual design he states: “The Lean and BIM processes and tools not only provide a much more accurate and sophisticated 3D visualisation capability, but also help evaluate the options from a range of criteria set by the client.”

This seems to echo an anti-design sentiment because conceptual design is something that needs to be “contained” and it is favourable that once a design has been formed under BIM it will not change: “Through parametric design and collaborative processes, the value loss is minimised when the conceptual design is passed along to later stages.”

Most architects understand that iterative design processes don’t involve a loss of value as the design proceeds. There is nothing wrong with drawing.

Myth 4 : BIM is suitable for all practices: large and small.

Small service firms, like architects and other consultants, are critical in fostering an industry wide adoption of BIM. The industry structure of architecture in Australia is heavily weighted towards small firms and for this reason the uptake of BIM in these firms is important. Small and medium sized architectural firms make up the majority of the market for architectural services. According to the Australian Institute of Architects (AIA), there are currently approximately 3000 architectural practices in Australia with approximately 11500 members of AIA. According to the Worldwide Architectural Services Industry report in 2012 there were a total of 1594 architectural firms in Australia. There are 1219 Sole practitioners, 525 firms with 2-5 members, 121 firms with 6-20 members and 26 firms with greater than 21 members, of which only 2 have more than 50 members.

Proponents of BIM claim BIM overcomes some, if not all, of the integration problems of traditional procurement. In theory, in BIM there is more rapid co-ordination as the BIM model develops. But, for small architectural firms the range, complexity and cost of different software tools which enable integration between design and construction creates huge demand in terms of skill sets of staff; small offices tend to adopt one software program and then adapt all aspects of their design and design development workflows to this program within the office. This implementation usually requires a degree of customization which puts pressure on a small office’s IT infrastructure, technical skills, workflows and business processes. Arguably, larger offices can more easily deploy, co-ordinate and implement BIM with design workflows.

Questions for small architectural firms

In small practices project roles and relationships within teams necessitates an examination of resourcing, technical support, and workflows as BIM teams evolve (Sing et al 2010). For small architectural practices the use of BIM raises a number of significant questions: Do architects simply design the forms for BIM consultants/engineers to create useful models from? In other words, will BIM systems integration and collaboration bring about the erosion of architecture as a disciplinary specialisation? How can parametric design and generative modelling tools be matched to BIM protocols?

With the rise of new fabrication technologies in the construction supply chain how might architects link the data in their BIM models to these new methods? Moreover how can we measure the costs and benefits of the use of BIM in small practices? What are the processes, techniques and protocols that Small and Medium Enterprises need to adopt to keep their services viable in a marketplace where the necessary tools and skills are becoming inaccessible?

BIM attempts to overcome some of the integration problems of traditional procurement. In theory, in BIM there is more rapid co-ordination as the BIM model develops. But, for small architectural firms the range, complexity and cost of different software tools which enable integration between design and construction creates huge demand in terms of skill sets of staff; small offices tend to adopt one software program and then adapt all aspects of their design and design development workflows to this program within the office. This implementation usually requires a degree of customization which puts pressure on a small office’s IT infrastructure, technical skills, workflows and business processes. Arguably, larger offices can more easily deploy, co-ordinate and implement BIM with design workflows.

Often, small practices struggle to convince clients that investing in design or design development is worthwhile. Design and design development is often seen as being too expensive and the end benefits cannot be quantified. As a result, the underlying schema of design and construction solutions are locked into too early and later reiterative processes, or design rework, is seen as being too late to pursue. However, one of the tenets of BIM based procurement is the ease of co-ordination and concurrent use of BIM with collaborative teams during early design stages. This is certainly the case in the BIM centred Integrated Project Delivery model and yet few studies have examined how small architectural firms might account for the benefits of early stage collaboration with BIM in these new procurement models. Barlish and Sullivan (2012) note that”there is a void regarding the measurement of project changes and outcome with respect to BIM utilization”.

The BIM research that we need

It is a pity that we do not have a BIM mandate in this country as it would certainly help drive much needed research in this area. At the moment there is no BIM research focused on small practice. Given that most architectural practices are small and that many architects are already on the BIM bandwagon it is more critical than ever that practical BIM research is funded and undertaken. This research should:

- Identify the critical success factors that support BIM adoption, implementation and collaboration by small Australian professional service firms.

- Describe and map the organisational structures, IT infrastructure and business processes necessary to the successful adoption of BIM across the practice lifecycle in small practice.

- Compare and then identify the interdependencies between parametric and digital modeling and BIM in early design stages and the later design development and documentation.

- Identify the potential cost and benefits and productivity gains of BIM implementation in small practices.

- Establish how the implementation of BIM shifts risk allocation in projects for small practice.