Robin Boyd’s Space Tube, designed for the Australian pavilion at Expo 70, was a commission that came at a time when Boyd’s practice was struggling to make ends meet. From mid-1968 through to Boyd’s death in October 1971, his practice consisted of mainly residential houses and some more speculative projects. Amongst these projects, the Expo 70 commission was one of Boyd’s more significant commissions because of his use of multi media.

For todays architect’s multi-media technology is ubiquitous and Expos in the 21st century are mostly hyped up trade shows. Expo 70, the site of the Space Tube, in Osaka Japan, was the culmination of the 1960s neo avant-gardes dreams for architecture aligned with futuristic and universal values. Expo 70 crystallised the experiments of the 1960s neo Futurist avant-garde even more so than the previous Expo 67 in Montreal; this was perhaps because of the influence of the Metabolists who were directly involved with the planning of the many of the exhibits at Expo 70. (1)

Original sketch of the Space Tube from the Boyd Archive at the SLV

In general media coverage and most publicity photos, Boyd’s space tube is generally overlooked in preference to the “coathanger” structure of the Australian pavilion designed by the Government architect James McCormick. The Space Tube gained very little publicity from either the architectural press of the time or historians since. This is surprising given that it is one of Boyd’s most significant later commissions. The cost of the project, in 1970 Australian Dollars, was then estimated to be $700,000 and Boyd’s fee for the work was to be $75,000 (2 ). More importantly, it was a commission which was actually completed; of the 28 or so commissions that Boyd received from 1968 until his death, 7 were domestic commissions and 13 were speculative schemes. (3)

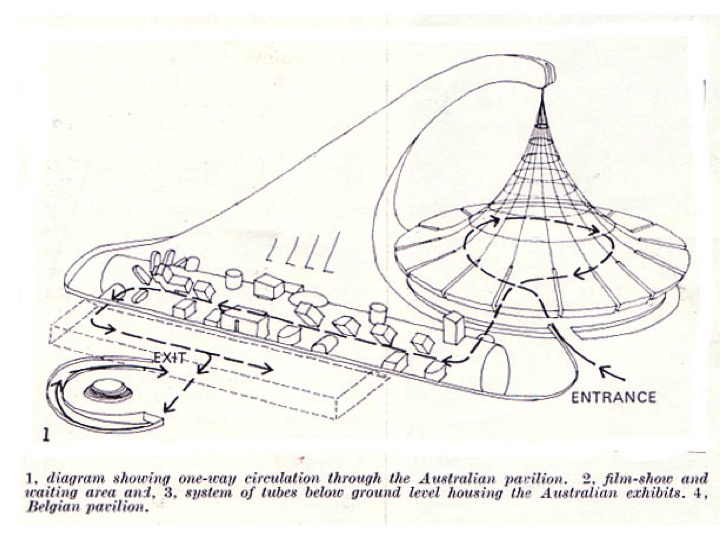

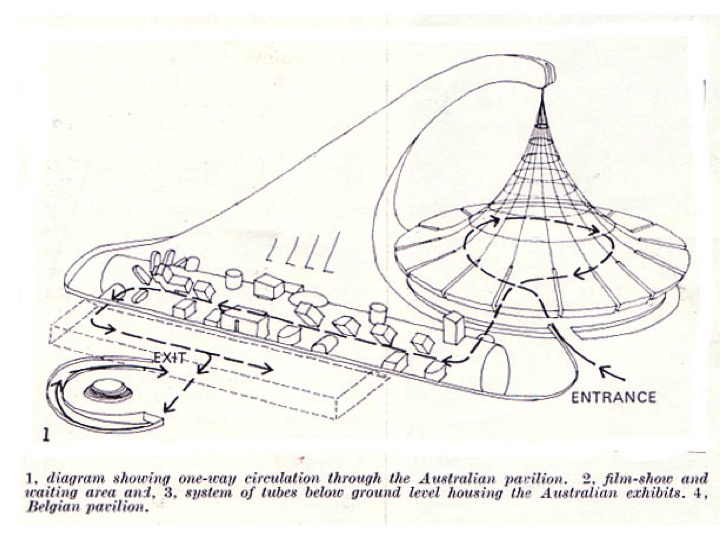

As the Australian Expo 70 exhibits architect Boyd was responsible for the planning and circulation of the interior exhibition area, principally within the space tube. Boyd, in consultation with the Commonwealth Government committee overseeing the project, proposed that the exhibit would have four subject themes: “Man, Man and Nature, Man and the Man Made, Man and Man”. It was intended that these themes would divide the space tube or tunnel into four parts, which would then contain 19 exhibits (4). In notes for an early press release, Boyd makes note of these display boxes, which were to be built in Australia before being shipped to Japan, to be “simply bolted on and plugged into the power supply.”

The experience for the visitor within the tube itself was designed as a sequence of experiences controlled through movement. Boyd’s intention was that the motion should be barely noticeable. According to Boyd, “[t]he function of the moving platforms is not to excite or even to relieve the feet. Their main function is to give control.”(5). Through this use of multi-media technology, the architect was able to control the flow of visitors through the space, and hence “present a sequence of exhibits, knowing that the visitor can view them only in that sequence.” After leaving the first crush space and stepping onto the travelator, the visitor was presented with a view of the entire tube for the first time. As the opening of each display was inset from the tube surface and arranged at a right angle to the axis of movement, all that could be seen was a series of bright lights and colours shining onto the visitors ahead.

In the final scheme there were 20 displays or subject areas in all. Each display or subject area was comprised of up to four display boxes, arranged radially around the tube. The visitor was moved past the displays by means of twin moving travelators which positioned the visitor’s eye level roughly in the centre axis of the tube. The travelators were supported from below by a minimum of structure, to allow an unimpeded view in all directions from the moving platform. The tube itself was made from “Gunnite”, a form of shot concrete on mesh reinforcing which created a thin shell. Attention was paid to the finish of the tube, with construction drawings stipulating a smooth, uniform finish on the outside surface and a matt black “acoustic surface” on the inside. The tube’s status as a design object was as important for Boyd as its role in presenting a view of Australian society.

Boyd was also responsible for the design of what was termed “technamation effects”. This was a multi-media technique achieved by projecting from two or more lights or projectors onto a polarised screen. As the viewer moved past the display, the screen would shimmer and ripple with colour and light. These effects were incorporated in a variety of ways into six of the display boxes. The best example is exhibit 17C, ‘Night City’. A model of a city block in exaggerated perspective was fitted on top of the polarised screen. Beneath the screen were six projectors mounted in opposing directions, creating the illusion of night traffic through moving red and white lights. What was otherwise a quite simple and almost dull model was in this way enlivened through animation. However, instead of a moving image or mechanical device, it was the viewer in motion which brought these displays to life. Visitors within the Space Tube were thus tangled in a complex set of visual relationships. The layout of the displays, in particular their height and angle in relation to the visitor, was one method used to control and organise these views. For example, the displays mounted horizontally (in the cardinal arrangement referred to above) made use of the level horizon line to suggest an equivalence between the visitor’s gaze and the subject matter. For instance, in exhibit 13C ‘Repco Brabham’, a cutaway model of a Formula 1 racing car is surrounded by a projection screen showing the car driving around a track. The view is arranged so that the visitor watches the track from just behind the car as Brabham makes his lap.

In contrast, the displays mounted at 45° to the horizontal present a more varied set of views. The displays below the walkway, such as 2C, 2D, 6C and 6D, present stylised views of the abyss – the mine, soil and what Boyd referred to as “the beasts in the pit”.(6) The circular frame of the display openings emphasise the detached and special view, appearing to be the viewfinder of an enormous microscope in exhibits 2C, ‘Some of the Body’s Microscopic Enemies’ and 2D, ‘Defence Cells Emerging from a Lymph Node’. The displays above the walkway more often include images of authority figures as part of their design. For instance, in exhibits 2A, ‘Immunology’ and 2B, ‘Organ Transplants’, circular screens were included which displayed projections of Gustav Nossal and Macfarlane Burnett, respectively. These images literally and figuratively look down on the visitor, countering the visitor’s gaze. These two displays include another recurring motif of Boyd’s design, the life-size transparent acrylic mannequin. A toy called “The Visible Man” and a teaching aid developed at the University of Michigan called “TAM” inspired Boyd (7). Both were human figures created with a transparent skin which revealed the organs inside. Boyd’s use of figures and bodies seems more scientific and anatomical than overtly erotic; however the experience for the visitor was doubtlessly voyeuristic (8).

Boyd was also central to the design and production of all the film, visual sequences and sound effects. He specified in detail the subject matter of each sequence, and personally chose the images used for each slide and film sequence. Though concentrated in the final displays, visual and multimedia effects were used throughout the tube as the central element of most displays. This was probably one of the largest and most extensive Australian multimedia projects of its time. In Boyd’s own words the purpose of the displays was to “capture the eye and the ear with light and colour and movement with music and sounds with 28 movie projectors and 46 synchronised slide projectors with hundreds of fluorescent tubes and 200 incandescent lamps.” (9). Circular screens were incorporated into most of the displays. Some of these screen arrangements were highly complex – for instance, exhibit 7B ‘Asian Aid’ was composed of six circular screens at the end of tubes housing a slide projector, each of which slid forward into the main space to reveal captions and subsidiary information printed on the side of each tube. Exhibit 3 ‘Tennis’ was made up of two projection screens facing one another across the tube, showing two players – Lesley Hunt and Yvonne Goolagong – playing a game above the visitor’s heads. Exhibit 17A ‘Ballet’ made use of moving screens, variable focal lengths and multiple projections to create a complex sequence of images (10). Sound effects were synchronised to visual cues for most of images, all of which were described and stipulated by Boyd. The Australian composer George Dreyfus was responsible for composing four variations of the pavilion theme, which were played at equal intervals along the tube.

The motion of the viewer through the tube constantly reinforced the logic of inevitability and progress within the subject matter of the exhibition material, and vice versa. For example, in Exhibit 20, the ‘abstract colour image’ designed in association with J.S. Ostoja-Kotkowski, was intended to literally be the “light at the end of the tunnel… visible all the time that the visitor is in the tube”(11). In effect, it was also a visual echo of the kaleidoscopic sun of first exhibit. From the very beginning, the Space Tube was thus a passage from a red/yellow stylised contemporary sun to a blue/green argon laser ray abstract future, toward “an absolutely explosive visual phantasmagoria in 3-D ” (12).

Of course this all makes me wonder if Boyd had at some stage taken LSD. Boyd’s thematic explorations certainly mark him as an architect of his time. But the design for the Space Tube does hint at the media driven technological future architects now find themselves immersed in (13). The degree to which contemporary architects have the same control over, or experiment with, new media technologies as Boyd did is debatable. Boyd may not have actually taken acid. But it would be nice if we could direct such an accusation at contemporary Australian architects a bit more often.

This is an edited version of a conference paper co-authored with Simon Wollan.Peter Raisbeck And Simon Wollan Boyd As “Bower Bird”: Robin Boyd’s Space Tube And The Global Avant-Garde. SAHANZ 2003.

NOTES.

1. For details of Expo 70 in architectural magazines see the entire issues of: Architectural Design June 1970 especially p 271 for comment on the Australian pavilion and Japan Architect 1970 Vol 45 N0. 5/6-164 see especially Koichi Sone, Sei Oyuki, and Yuji Morioka, “Moving Walkways and Urban Traffic” as well as p. 69 for a comment on Kikutake’s Expo tower.

2. Fee agreement for the project was signed on the 22nd of October 1968; to be paid in monthly instalments as the work proceeded. For this fee, Boyd’s brief was to design the Space Tube and its display cases in a way which would depict Australian life and industry to a primarily Japanese audience. The Commission also extended to producing and managing the construction of designs for the merchandising which was to be associated with the exhibit. Refer to Box 104, GRB Archive, State Library of Victoria.

3. His most significant civic architectural commissions during this time were Churchill House, exhibition designs for the Australian Chancery in Washington and the ”First 200 years exhibition” in the foyer of Harry Seidler’s Australia Square building.

4. In the original proposal the exhibits were numbered from 1 to 19 with the following subject titles and in the following order: origins of humanity, the battle against disease, science of the mind, enjoyment of life, Australian invention in agricultural technology, Soil and Water, Exploring and preserving resources, Exploring the Universe, utilization of Polar Regions, Transportation, Modern Living, Urbanisation, Automation, Language and Literature, Communications, Fine Arts, Lively Arts, Australia-Japan Relations, The Film. Refer to Box 104, GRB Archive, State Library of Victoria.

5. Robin Boyd, “Australia at Expo 70 for Walkabout” , undated text, Box 103 (c), GRB Archive, State Library of Victoria.

6. Letter from Boyd to Prof. G. Nossal, 11 July, 1968. Box 103 (a) GRB Archive, State Library of Victoria.

7. Letter from Boyd to J.P. Tyrer (Acrylic Industries), 7 October, 1968. Box 103 (a) GRB Archive, State Library of Victoria.

8. Further work, which is outside of the scope of this paper, is required to fully establish how Boyd fetishised these figures as objects, and the more general effects of the technological gaze within his designs.

9. Robin Boyd, “Australia at Expo 70 for Walkabout”, undated text, Box 103 (c), GRB Archive, State Library of Victoria.

10. First, a film loop showing dancer’s legs was projected onto the front screen, nearest the opening to the tube. Next, an image from a slide projector appears small and out of focus on a screen behind. As this screen moved forward the image enlarged and came into focus, before again going out of focus and diminishing in brightness. From the visitor’s point of view the slide image passes through the film image, literally deepening the visual field of the screen. Refer to Box 100/3, GRB Archive, State Library of Victoria.

11. Letter from Boyd to J.S. Ostoja-Kotkowski, 16 July, 1968. Box 103 (b) GRB Archive, State Library of Victoria.

12. Letter from Boyd to J.S. Ostoja-Kotkowski, 9 October, 1968. Box 103 (b) GRB Archive, State Library of Victoria.

13. This compression of time and consequent distortion of space also appeared in individual exhibits. For instance, exhibit 13D ‘Shipbuilding’, displayed a model of a ship growing from blueprints to steel structure to dry-dock construction to finished bow steaming steadily ahead through a technamation wave. However, instead of showing each ship in sequence, each stage occurs on a portion of a single hull, giving the sense that the ship is impatiently sailing through time into the future. That this exhibit is the only one mounted directly below the visitor, between the two travelators, ensured that this movement was aligned with that of the viewer.