All that remains of the Western Shard at Federation Square is an imprint on my Shard protest t-shirt.

In case you missed it the Open House Melbourne debate regarding the Apple store at Federation Square took place last week. I watched the live stream at home on my Apple iPad. I couldn’t get a ticket and something else was on at work at the same time. But I decided to stick it out and settled down with my APPLE Gold iPad Mini (yes, terrible I know to admit, obviously I am some kind of unwitting sucked in APPLE consumer; Oh, and I should say I am typing this on an Apple Power Book that is owned by my University).

I hate getting on bandwagons no matter the cause. Cause orientated bandwagons always seem too cultish and clubbish for my liking. But hey, at least I was involved with the effort to Save the Shard. I still have my T-Shirt to prove it. What worries me now are the echoes of that debate in this one.

I watched it on the live stream for more than the entire 2 hours. I am thinking the whole thing is going to make a great case study for my Design Activism course in September.

Its great Open House Melbourne organised this debate. It was seen by many as a mature debate around issues of urban design and public in our city. But, if the debate was mature, then we can also ask, how nuanced was this debate ?

So here is everything you need to know about the debate at Federation Square in 10 easy to digest points.

1. Let’s face it the Yarra Building at Fed Square became a bit awkward.

As hinted at by Donald Bates one of the architects of Federation Square, in his debate speech. The Yarra building never was the best bit of Federation Square, it was worth a try at the time, as a commercial space, so why not change it now? Why not redesign the Square? Or should we just keep the Yarra Building as a piece of so-called heritage?

2. Some people like to say the word Activation a lot.

I must have done my post-graduate urban design degree so long ago at RMIT that it was before this activation word came into vogue. Donald Bates mentioned it a few times but Ron Jones on the Anti-Apple side mentioned it a lot. It even made the internet tabloids.

Its zombie urbanism concepts like this that a sliming (or slimeing?) our cities with low-grade commerce. Does “activating an edge” mean putting in little coffee shop, or kripsy kreme, tenancies all along a so-called urban “edge”.

3.Politicians still need to figure out that community consultation processes for large-scale projects are needed.

I think Cr. Ron Leppert was able to set out the case for the failure amongst our political class (the non-greens class) to adequately consult and to be transparent. It was great when he kept saying something along the lines of “I am not an architect”, but I am still going to tell you how to plan the city. That was so “plannersplain.” Designing planning schemes without an architectural perspective = more zombie urbanism. Read about it here.

4.The Committee of Melbourne elites have yet to develop a more nuanced argument than the zombie concepts of Melbourne 4.0.

The Committee for Melbourne CEO Martine Letts, ably outlined the standard neoliberal position: more change, more disruptive technologies and get ready for more global competition. We are all on this hamster wheel. But maybe the Committee for Melbourne might have more success in these matters if it wasn’t full of so called “movers and shakers.” Let’s see a few “bogans” on their board. This is definitely a group that could do with a dose of real people and learn about community development and consultation. God help us when F2, (neo-liberal speak for Federation Square East) gets going.

5. The Victorian Government Architects Office needs more funding and independence.

Yes ! That might help get some transparency back into these processes. When will politicians stop listening to Treasury and listen more to architects?

All too obviously, this situation is the product of the autocracy, elitism and lack of transparency when it comes to the procurement of major civic projects in our nation. Architecture is too often sidelined. But something like this is bound to get a backlash. When will our political classes and neo-liberal elites figure this out? It was the same at Sirius in Sydney and there will be other examples in the future.

6. No one from Foster’s office or evil Apple seemed to be at the debate.

I have written about the Foster design for Apple HQ here. As someone noted in the Open House debate when these stars come to our great southern land they don’t necessarily do the best job. Usually they just do second rate job then fuck off back to whence they came (Lab Architecture Studio was actually an amazing exception to this).

7. The design of Federation Square didn’t just happen

I fear that many in the audience didn’t know this (maybe the audience was packed out with too many of Ron Leppert’s Green’s party planner mates and that’s why I couldn’t get a ticket), but the design actually evolved and emerged over time. Yes, architects actually design things through iteration. Designs don’t just pop out of architectural heads fully formed. Donald Bates said something like this and its worth quoting from my rough debate notes:

“This is a Drawing showing one tenth of all the iterations of the design process. The design developed by iteration and possibilities emerging. It is about a design of relationships and not specific objects. The fixation on objects is not embedded in the DNA of the Square

8. It is a hate the big brand thing

It is correct to say Fed Square is not retail Chaddy or Bunnings. But it doesn’t matter because according to the no case, Apple, will make Fed square into a giant Shopping Mall. A huge giant giant shopping mall. Just like they have in the suburban badlands. They will sell you stuff and every Insta photo in Fed Square will feature them. It’s a brand thing the No-Apple side is fighting against.

In response to the Apple proposal its easy to rail against the perceived evils of the big brands. Apple’s personal consumerism, its awful tax regimes, its blind technological march to the singularity. But what does that have to do with site specific architectural arguments in this instance?

9. The Koori Heritage Trust gets a much better deal out of this proposal.

Shouldn’t that be the highest priority for Federation Square as a public and civic space? If it was me I would put KHT where the Apple store is supposed to go and Apple into the Deakin building. I would, if I could, decolonise the square and let KHT own all of it ! Maybe thats what we should be thinking about rather than the populism of big brand hatred.

10. Its train wreck

This issue is a train wreck of big brands, naive and not so naive political populism. Not to mention, architectural ignorance, conflicting theories of architecture, planning and urban design in our civic politics. Space prevents me from writing how we got to this point. It may sound strange but I partly blame that huckster Jan Gehl and his slippery urban design populism for watering down our urban theories and analytical instruments. I think the crazy comitteeee for Melbourne has a lot to answer for. Check out what they thought about the minimum apartment standards. A veiled attack on those standards in the name of a pro-development flexibility. Yet, this is a group that claims to be all about sustainability and future liveability.

Outrage cycles and populism

It’s so easy to be populist in this social media age. Easy to rev up the shock jocks and the tabloids. Perhaps this is why it’s the No-Apple bandwagon that also worries me in this debate. In embracing populist notions of public space, architecture and urban theory are too easily erased from the public discourse. This has what has happened in regards to this issue. Digitised Outrage and Outrage and Outrage that blunts any real analysis of the plight of our civic spaces. Paradoxical when all the genuine and self serving outrage is facilitated by Apple devices. Architecture and any deeper architectural and urban arguments get swamped.

The architectural and urban arguments for Apple, as presented in the debate, were analytical, nuanced and refined (to echo the Victorian Government Architect) and actually grounded in architectural process. Arguably, it is the architectural argument that bridges the complexities between architecture, urban design and the social realities of the mercantile.

Having said that, we also need to recognise that the position underlying the Pro-Apple argument, and indeed the original scheme, is based on a stream of architectural theory that has never really resisted, and always accommodated capital. There never was a secret about that in this city. So why are people upset now? No one screamed when QV was pillaged and privatised. Of course its because we all love Federation Square so why don’t we now listen to one of its architect? But do we really care about pursuing real public space and architecture?

It’s way too much like Hilary versus Donald.

It seems ironic to me but in a strange way the Pro-Apple team was a bit Hilary-like (actual experts, politicians and neo-liberals) whereas the Anti-Apple team employed Trump-like (or maybe John Howard) populism. A populist backlash that seems to be saying: we are the people, we are angry with the neoliberal and global elites, we are angry about the public spaces in our city, we hate the outer suburban shopping centres, and so WE should get to decide who comes to our Federation Square shores.

What a train wreck the whole thing is and I am not even sure the punters care that much. Because, after all is said and done, Federation Square has free Wi-Fi.

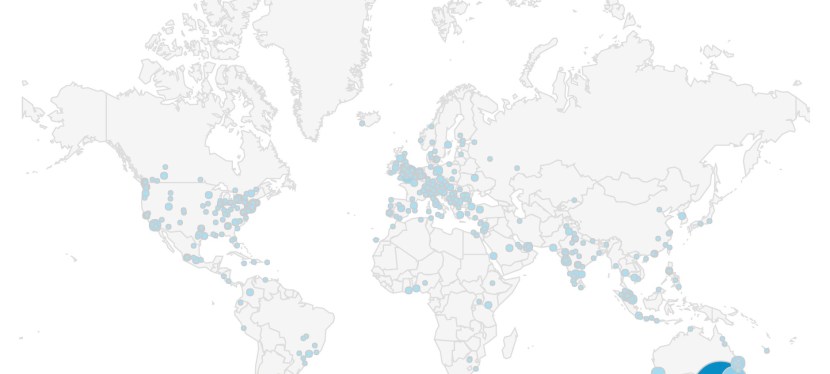

I know many international readers of this blog will imagine me lolling about on beaches, surfing the waves, driving across the dunes, wrestling Crocs, or drinking in the pubs. Of course when I look at the Instagram and Facebook feeds of the other architectural academics I know they are all having a great time over summer. Maybe the new social media landscape is what is giving people the impression that architectural academics are slack arses who do very little when the students are not around. On Instagram my fellow academics are on beaches, in forests and far flung places like Central Java, Coolangatta, and New York City. Mostly they all seem like they are eating a lot of gelato ice cream and chugging down the French champagne. But that’s only how it looks.

I know many international readers of this blog will imagine me lolling about on beaches, surfing the waves, driving across the dunes, wrestling Crocs, or drinking in the pubs. Of course when I look at the Instagram and Facebook feeds of the other architectural academics I know they are all having a great time over summer. Maybe the new social media landscape is what is giving people the impression that architectural academics are slack arses who do very little when the students are not around. On Instagram my fellow academics are on beaches, in forests and far flung places like Central Java, Coolangatta, and New York City. Mostly they all seem like they are eating a lot of gelato ice cream and chugging down the French champagne. But that’s only how it looks.