Design Leadership requires the ability to be open and transparent about the way ideas and design knowledge is conceived, transmitted and fostered in the organisation. One thing that seems to hamper research across the field of architecture is a culture of secrecy. There are patches of this culture all across the topography of architecture. It manifests itself in a number of ways and at a number of levels. It might be the directors in a larger firm afraid of sharing information that is seen to have some competitive advantage. After all, if the cabal shares the premises of a firm’s competitive advantage that might mean exposing that knowledge as inconsequential. It could be the project architect who hangs on to project information and does not share it with others in the team. Better to keep them guessing or in the dark. It is easier not to explain anything. Or it could be the so-called design architect who refuses to reveal the sources or the inspiration of his conceptual ideas. After all, someone might steal those ideas and claim them as their own.

All of these shenanigans of secret knowledge, tacit and unspoken communication and preciousness are corrosive to developing an architectural culture that maximises design knowledge. The covens of design managerialism and secrecy, the power tripping of withheld project information, and the egotistical horrors of pathetic design ideas made more important by being locked in the head of the design architect. All of these attitudes make it very difficult to conduct research within the profession.

I am not really sure where this culture begins. Of course, the curricula and studio systems of the architecture schools as usual, can be blamed. Few subjects are devoted to leadership and organisational governance in architecture school curricula. No wonder the profession is struggling to maintain itself.

In these systems, without the right studio leadership, individual competition can be vain, petty and subject to the vagaries and whims of favouritism. We have all been in studios where we will never make the favoured circle. Design Leadership is not about simply reinforcing and replicating your own theoretical position or the way you were taught architecture. Nor is Design Leadership is not about positioning a design within systems of parochial politics in order to gain influence. It is not about designing in a way that positions you for a commission or a peer award.

To reiterate, Design Leadership is about maximising design knowledge in the most efficient, effective and brutal way possible. After all when the rubber hits the road and the project is besieged by clients, value managers, and contractors the design ideas need to survive the journey.

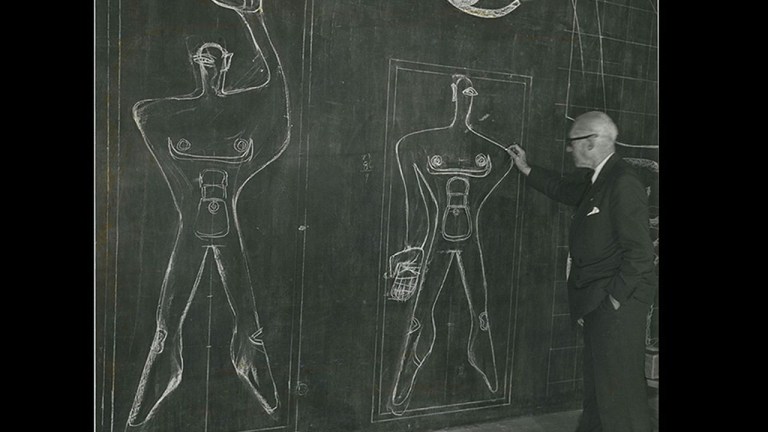

The continued glorification of the design genius, which I have written about elsewhere, only leads to a situation where the profession is riven by localised mystery cults. Each genius, whatever their stature, surrounded by acolytes along with initiation ceremonies, encouraged rivalries, different circles of access and knowledge. It all starts to sound like Trump’s White House. Better to be an outsider than in the cult. So here a four principles to creating a culture of Design Leadership in your practice.

- Make design processes visible

Design leaders have clear processes in place. These processes are visible, transparent and communicable. Design leaders understand design processes and how these processes work through team environments. Design Leadership requires generating design knowledge and ideas through clearly communicated actions and gestures. By doing this everyone in the team can pursue, develop and contribute to the design.

- Don’t hide design knowledge.

Hiding design information only creates islands of territorial power. The role of Design Leadership is to constantly posit design knowledge into the public sphere. Of course this sphere may the realm of the project team or it may be the consultant team. from different groups or individuals within the organisation It is not about hiding things away. If design are ideas are hidden they are not fully tested and may then crumble at the first sign of value management.

- Make designing inclusive.

Design Leadership does not require the trappings of a cult. It does not exclude or set boundaries around who can be in and out of the team. A collaborative team open to a range of design views is better than a team subservient to a single design view. Effective design leaders mentor and foster their team members. They do this is in order to make individual team members better designers.

- Create space for design.

Good design leaders are bale to create safe havens for the most extreme and seemingly kookiest of design ideas. This is because, Design Leadership requires teams that ask questions rather than teams that simply reiterate like-minded principles. Excellence in Design Leadership nurtures and fosters this questioning. Everyone should feel safe to ask the dumb questions in the design team.

- Creates more ideas than can be used.

This is the measure of great Design Leadership. Having a cauldron of ideas constantly generated and replenished as the project proceeds. Design Leadership means both generating and then managing design ideas as they proceed. Design Leadership means having the luxury to pick, choose and give life to the best of architectural design knowledge.

Architects need to change the way they approach Design Leadership and their own organisational structures. Architects need to more effectively manage their own pool of talent. What architect wants to sit in front of a computer second guessing what needs to be done? Worse still, is sitting in front of a computer knowing whatever you do is never going to be quite right, because you weren’t initiated into the favoured circle.

Now back after a brief Easter Break !