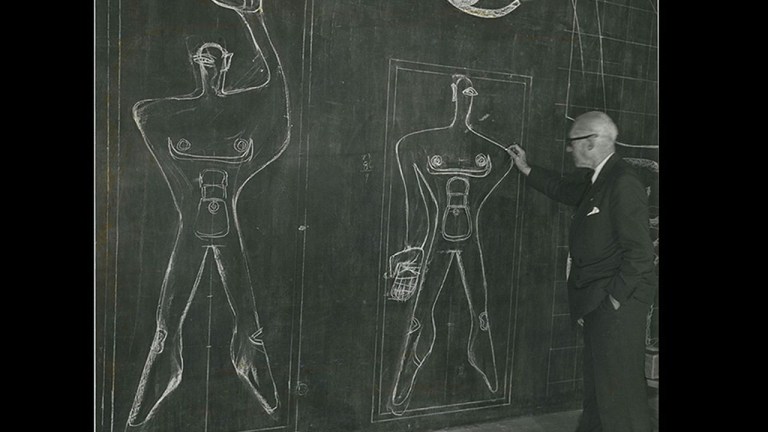

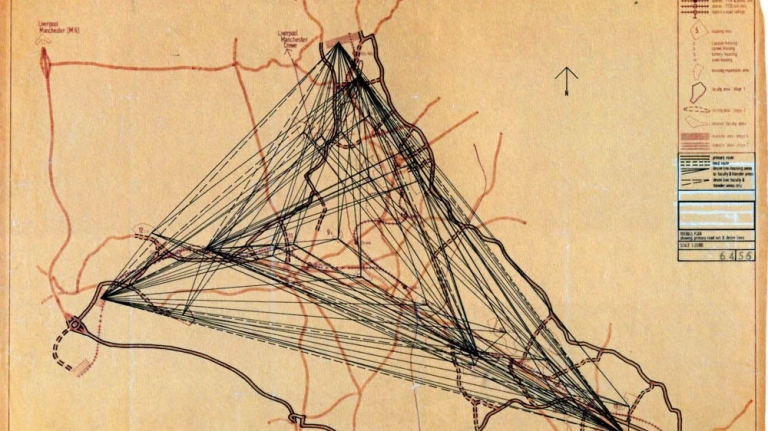

Sometimes I get to tutor, as in actually teach in front of students face to face, and a lot of the time it is fun. Another night in a practice tutorial I held up the three plans and a section of Corbusier’s La Tourette to the students and asked them if they could look at these plans imagine what the building was like in 3 dimensions. Some responded with an educated guess, but most just looked at me blankly. I then held up a trade breakdown of figures for a different project and asked them to imagine what these figures might also suggest about the three dimensionalities of the project.Hence, the seemingly perverse exercise of comparing some photocopied plans of La Tourette with a list of Trade Breakdown figures I suppose I was trying to indicate how “reading” plans are the same as reading a list of figures. More blanko looks.

Plans and Trade Breakdowns

But I then led them through the figures with a close textual reading as historians also do. I told them how you could “read” the trade break-down figures to understand what these say about the buildings final form and the opportunities buried in the figures for getting some design into the project. One student had the insight to ask me, “how might an architect stack up or shape the figures to achieve some design objectives”? Which in the real world, if you are not a so-called architect obsessed with project productivity and optimization, means having further opportunities to design as the delivery process unfolds.

Afterward, I thought about this encounter with the students and begun to worry if they had now lost the ability to read drawings or anything else for that matter. Although, that is a little harsh, and far be it for me to appear to be or seem harsh in my judgments (you only have to look at my last two blogs to see what a paragon of fair-minded generosity I am).

Plan reading blindness

Anyway, I then began to wonder if that is the case, if the students now ensconced in the joys of computers and Instagram had now lost the ability to read plans. And dare I say it, these plans are, what some of us might call “traditional plans” and sections. But reading and interpreting plans and sections and other documents is a critical skill that all architects should possess. If my hypothesis is correct, that architects are no longer teaching, or taught, how to read plans (and I hope it isn’t), it might nonetheless explain why the industry thinks that the skill base of graduates is declining. Is it any wonder if graduates are not learning actually to read, interpret, ponder or wonder about plan drawings.

What an architecture course is not

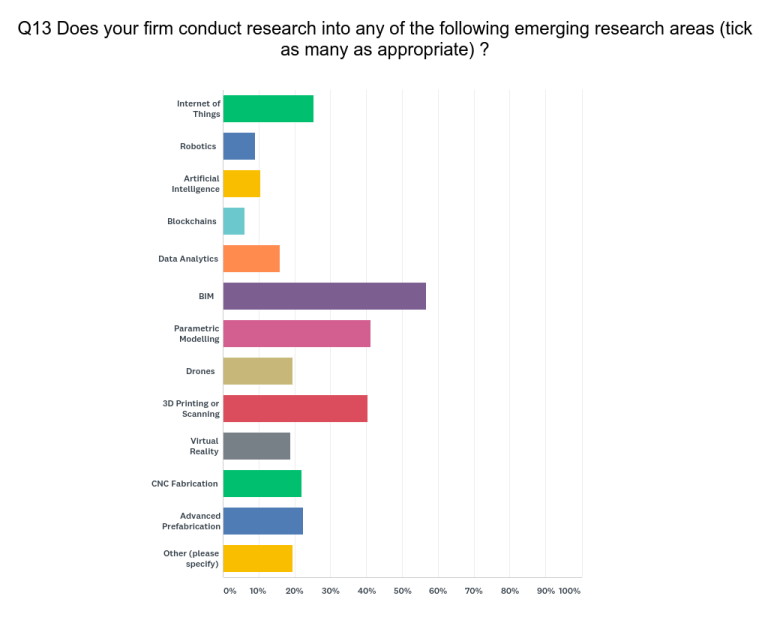

Same with digital graphics and the other evils of computing. I wonder if the problem is that interpreting or reading a drawing requires an attention span that goes beyond the ten milliseconds it takes to like an Instagram or Zuckerberg post. Then there is the obsession with just making stuff. Many schools are nowadays obsessed with making stuff. I suppose the highest planet of all this maker-spacey making seems to have been the AA’s DRL lab. That’s all fine and good but making stuff is not the same as learning to interpret drawings. Nor is the obsession with a computer or some other kind of digital graphics. You can’t build an architecture course around digital technologies and prefabricated construction and workshops. This isn’t actually an architecture course!

These algorithmic things are ancillary to architectural design and they always have been. I know you might think I sound like an old curmudgeon and that’s also part of the problem as well. The traditional-new polarity is a misnomer. All because a technique is new, or has a legacy, doesn’t necessarily mean it is either excellent or needs abandoning. Architects and educators have a responsibility to consider how new techniques should constitute and shape architecture. The problem with that proposition is that might mean thinking and arguing about architecture in a theoretical sense. What broad techniques, instruments or ways of thinking should we be encouraging in architectural education and through our industry bodies?

After a while, architects may not even know what a plan is. So here is an exercise that everyone might do to remedy the situation.

A remedy for plan blindness

So, If you an architecture student this is what you need to do. Its kind of like a mindfulness exercise for architects.

1. Find some plans and sections print them out.

2. Look at the plans for about an hour.

3. Lie down and think in your mind what these plans imply about the buildings three-dimensional form and materiality.

4. In your mind walk through the building.

5. Go to sleep.

6. Wake up the next day

7. Go and visit the building and see if it is the same as what you thought.

8. Write a few notes about the experience.

9. Repeat for a different set of plans.

Avoid the urge to skim around the internet or look at your phone while doing the above. It is entirely possible that all of that attention seeking digi distractions are making you a dumb and dumber designer. The problem is you may not even realize you cant read plans.