There has been a lot of chat lately about new models of practice. Increasingly, the scavengers and myriad tribes of architects that exist find it difficult to make their practices profitable in the face of intense fee competition and, what some have called, the economics of austerity. I have touched on alternative modes of practice in a few other blogs but I thought I would say a bit more.

No Silver Bullet

Foremostly, I am worried that practitioners think that there is a silver bullet or a simple solution to this issue. That we can wave a magic wand over the structure of their practices and it will all be better. I am worried that practitioners think that if only they had restructured their practice in a different way in the first place things would be easier. Yet, the legal and corporate frameworks for practice are normally quite limited within, and across different countries. There is no one way or legal “switch” that a practitioner can switch on or off if a practice is not profitable or not seeming to get anywhere. Changing the legal or financial structures may not change things. If you are not making money you are not making money.

The traditional models of sole practitioner, partnership or even company model appear to limit what architects can do. Some of the mega-firms, or Transformer firms, as I have denoted them elsewhere, seem more successful. They appear to manage ok, by virtue of being extremely large and having integrated service chains that provide a potential client anything; let’s not think too much about how these large firms might manage their taxation affairs.

Critical Regionalism

For many smaller scavenger and tribal practices there is still the dream of criticality at a local level. Of doing great jobs that people love in your own city, street or neighbourhood. Thinking about this reminded me that in the early 80s Kenneth Frampton argued for a new architectural culture based on critical regionalism. Frampton advocated an architectural culture and discourse that was resistant to what he saw as processes of universalization. Frampton argued that optimising technologies had delimited the ability of architects to create significant urban form. For Frampton, the work of critical regionalism a practice focused on, and grounded in local traditions and inflections, was intended in Frampton’s words to “mediate the impact of universal civilisation.

I think that much of Frampton’s dream has come to imbue much of what we value in Architectural Practice and design. The Pritzker prizes seem to go to regionally inspired and grounded architectural auteurs. In my country a lot has been written about the two main city based “schools” or traditions of work the Sydney School and the Melbourne School. But, I worry that as architects we have been boxed in and swamped by global capital and technologies while we clong to models of practice are focused on the auteur. I think the the dream of critical regionalism is something that perhaps masks the real situation: The continuing commodification of architetcural knowledge.

Exploring new models of practice.

A few years ago, I got my architectural practice students to do business plans for Social Enterprises. In other words, for enterprises that had a social purpose or profit. In my naivety I thought they would love doing it. The idea was to encourage the students to think about how they would use their architectural skills and knowledge to determine the nature of a new social enterprise. It was a way to hopefully get the post-graduate Master’s students to think, yes actually think, about different forms and models of practice.

The better social enterprise plans were encouraging. A number of plans aimed to address gender discrimination. One plan looked at commercializing feminine hygiene products in order to get homeless woman off the streets. Another group targeted the architecture and construction workforce by supplying sustainable personal protective equipment and then investing the profits to advance gender equality in the design and construction workforce. A few projects looked at issues around waste and recycling. For example, one project looked at recovering discarded food and food waste. One of the better social enterprise plans produced by the students was based on putting beehives into social housing estates and then harvesting, marketing and the selling the honey. Thus, employing some of the residents in the estates.

Thinking outside of the box.

But by and large most of the students hated the exercise, my student experience scores that semester tanked, and my academic masters wondered “WTF” I was doing. A practitioner associated with the school asked, “why are you doing business plans at all?” I think the social enterprise plan about the Bees was the one that really drove everyone nuts. Of course, it didn’t really help that I said in the Assignment instructions that: “There are no prescriptions for this assignment. On the basis of the business plan, you will be assessed as to how well your social enterprise will realistically establish itself, survive, and grow.”

So much for getting the students to think out side of the box and deal with high levels of ambiguity. This year we went back to business plans for the straight-down-the-line architectural practices.

Abandoning the old ways

If we are to talk about different forms of practice then I think architects really need to abandon their pre-conceived notions of what practice is. There is no magic solution. We need to use our learned creativity and design thinking skills to embrace new ways of doing business. Not everyone is going to be an architect with a capital A. We need more beekeeping ideas.

A recent exhibition at the CCA, and now travelling, suggests that historically alternative practice doesn’t always have to centre on the single genius. At any point in time architects have always sought to explore new models of practice and escape the constraints that beset them.

Thankfully, there have been those in recent years who have broken out of the old moulds of architectural practice. Collective and collaborative action is a common theme on my short list. Notably, and not in any order, the following spring to mind:

Assemble, Parlour, Forensic Architecture, ONOFF, Sibling, R&Sie and Group Toma.

These examples suggest, a wider range of practice, as well as the different ways, that architects might now practice. I am sure there are also other examples and I will add to this list over time. Contact me if you know of anyone. But the final upshot is this: Architects really need to think about these new paths. Because, architects can’t be sure that the old ways are going to work for much longer.

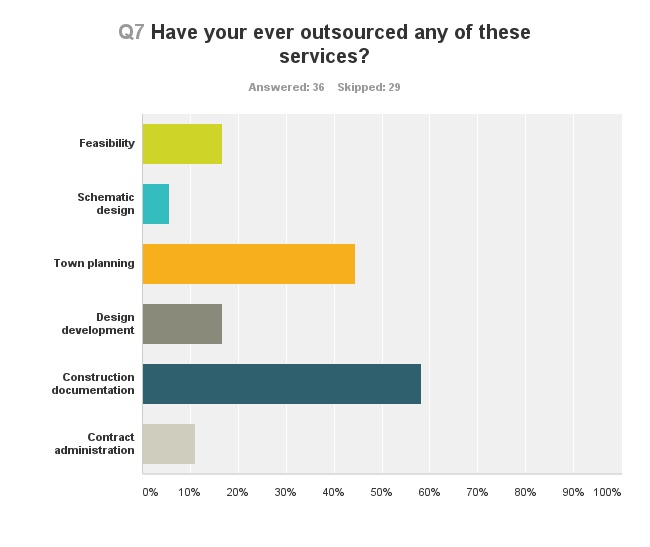

Chart 1: Outsourcing is widespread

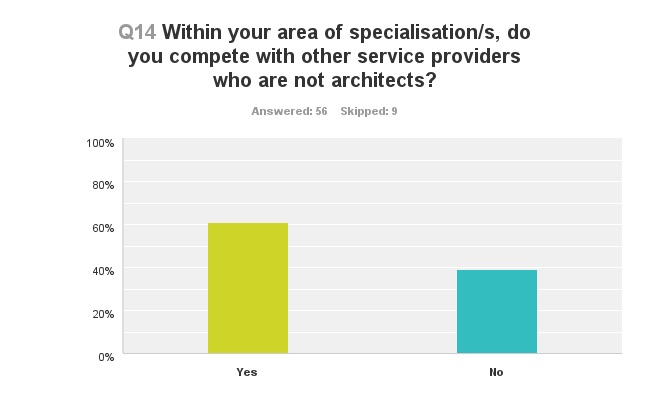

Chart 1: Outsourcing is widespread  Chart 2: Competition is Intense

Chart 2: Competition is Intense