Now that Trump has abandoned the Paris climate agreement what can architects do? Are architects doing enough? In the face of the prospect of two-degree global warming I would suggest that we architects need to reconfigure and question our current professional certainties. The issue of global warming and its relationship to architecture is one that warrants being written about in a polemical fashion.

Enchantment

I fear that we architects are consumed and distracted by a narrative of enchantment. A discourse that distracts us from developing a more radical narrative and leadership in the face of climate change. As I suggested in a previous blog this is narrative has a focus on utopian poetics; a naïve poetics that should be dammed for its lack of irony and unself-conscious perspectives. As Urban-Think Tank have proclaimed we need to forget utopia and need to focus our perspective on the unfolding, and catastrophic, realities of the Favela cities and informal settlements. These are the cities which will be impacted the most by a warming atmosphere.

The fantastic technologies, futuristic cures and emerging intelligent processes that circulate in popular culture and social media have little immediate impact on the realities of day to day practice; nor do they touch the cities that are driven to highrer densities as a result of volatile capital flows. Why have architects and urbanists so thoroughly embraced the densification of cities and the global urbanisation mantra?

Architects need to avoid the comforting fairy tales and cures of technology. We also need to avoid the self-comforting warm slosh of green of sustainability. Don’t get me wrong I am all for innovation and Futures thinking. But I am not for a distracted profession that is naïve when it comes to arguing and debating different alternative futures. Our futures should not be simplified and depicted as picturesque renders of flooded cities; or worse still floating cities that are little more than polluting cruise ships; or the escapism of outer space habitats.

Yep, the robots, and articial intelligence is coming, but that doesn’t mean architects need to unthinkingly embrace emerging technologies as the next best thing to ride. The robots and drones will probably kill us.

More activism

Architects are uniquely placed to address the above issues and the serious issue of a warming world. But in order to do so architects need to be more radical in their activism and policy stances. Our discourse is too conditioned by tropes that imply adaptation, integration and accommodation, rather than militancy, in the face of a looming disaster. Words like sustainability, adaptation and resilience need to be abandoned and recast. This is a salvage operation in the face of mass extinction and should be seen as such. It should not be too strident, too polite or too crazy to discuss things in these terms.

Architectural theory

Architects also need to recast their theoretical instruments. The apolitical and abstract theories and debates that emerged out of the pedigreed schools of the American East coast in the early 80s no longer have any utility. In practice these theories have too often supported neoliberal capitalism. We need new theories that encompass diversity, difference, ecological realities and contest neoliberal urbanism. As some have suggested we need to abandon the dictatorship of the eye.

Architectural education needs to change and orientate itself towards developing a scepticism about emerging technologies. As argued by myself elsewhere the production architectural knowledge needs to be privileged over the production of the physical object or building. We need to teach young architects how to manage data, information and knowledge.

If design research is to mean anything then we need to argue about how we can measure and qualify its contribution to architectural knowledge. The latest funky or sustainable design requires a theoretical infrastructure and argument that establishes how design contributes new knowledge to the architectural canon. Just saying and making the claim that a particular design is design research is not enough.

Architectural leadership is important in the current age of barbarians and fragmented truths amidst the swirl of, what Debord designated, as the Spectacle. But in order to exercise that leadership architects need to avoid the easy seductions of a naïve and seemingly idealistic poetics. Only then will architects help to shift the narrative in favour of the Polar Bears.

google-site-verification: google27302ff7933e246a.html

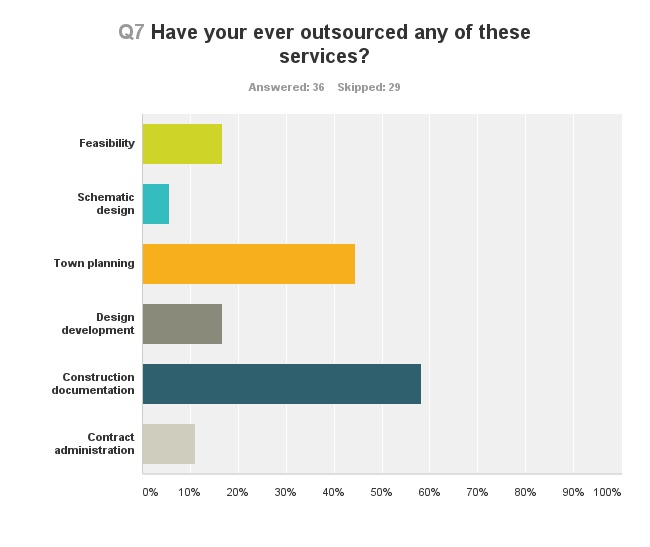

Chart 1: Outsourcing is widespread

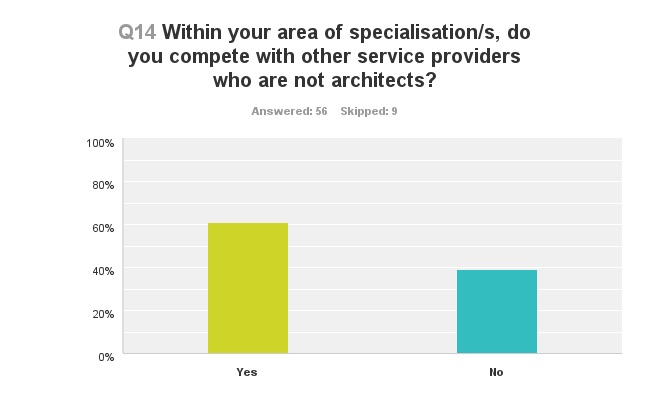

Chart 1: Outsourcing is widespread  Chart 2: Competition is Intense

Chart 2: Competition is Intense