When architects fail they usually seem to fail big time. The tabloid media loves to jump on that large, or prestigious, or prominent architectural project that blew the budget, or leaked, or fell down or little fragments of it fell off into someone’s batch brew. I am sure we can all think of something like that. Then of course there are the Foxy news tabloids aligned with the small minded burghers who declare a building is “ugly.”

Of course, not all of these so-called headline failures are the actual fault of the architects. More often than not it is the people driven by the cheaper, faster and crappier mantra who love to blame architects.

For the most part architects spend their life trying not to fail. There is a lot of pressure on architects to get it right. As system integrators, perhaps the pre-eminent system integrators in the AEC industry, we are often too busy connecting, juggling and generally trying to avoid the fails. Think of all of the things we architects need to consider, adjust and integrate: planning, regulations, contracts and the whims of client.

But, one of the things we should remember is the necessity of failure. Architects need failure to innovate and failure is an essential factor in both design, and dare I say it research and development.

Radical design innovation or new design research knowledge, knowledge that questions the status quo, doesn’t come about by playing it safe.

- Good architects know when to fail.

Designers know when they need to explore the, deliberately bad or ugly and even less optimal option. They know when to be deliberately perverse. They know that by relaxing the process of their own design logic they can produce a design option that is less optimal. They can learn from this. Great architects now when a less optimal design option or design pathway can help the further iteration of the next design option.

There might even be aspects to the deliberately perverse or failed design option that could be salvaged. It might even be really amazing.

- Beware of architects who never fail.

For these architects, everything is a relentless pursuit of the ‘perfect” solution. This is because everything the bad designer does, every gesture, flourish and design utterance is perfect. These are the sorts of architects who will have you sitting around watching their every flourish of the pencil.

- Architectural design is not about controlling every step.

Architectural design is not about getting it right all the time. An overt focus on a design logics of correct sequencing and conceptual ideation ultimately leads to boredom. Sure, we all need to think straight as designers, but making that the only goal of the design process leads to a cult of academicism with little room to advance.

By generating failed design solutions, you will have, for comparison and analysis, more elements in that design portfolio part of your brain. The aim is to build a bank, even if it is only tacit info in your own brain. Your design brain should be full of design practices, approaches, methods, norms and concepts.

A less than optimal design approach, design element, or design solution may not be suitable for one project, but could be well suited to another project. It might even prompt a few more ideas.

The kind of failure I am describing, encourages the development of a range of design solutions.

- Design Research should not always need a “purpose” or be of some instrumental use.

This goes for any type of research actually. But, design research is a risky enterprise. It wouldn’t be research if we already knew the answers or the outcomes. Often as architects we are so intent on making the trade-offs we need to make in the design process that we forget about the notion of disruptive designing.

Sometimes we need to pushback against the clients, the planners, and the contractors. This may mean that we are in a situation where we risk failure. But unless we do this our design research and the resulting innovations may be little more than orthodoxies. The same old same old.

Radical design research and design innovation risks and then manages the potential of failure.

- If you are always getting it right as a designer then rethink.

Pursuing failure avoids design hubris. There is always the post-rationalization impulse as a designer, the confidence to never admit a mistake, to always have a reason; but you don’t always need a reason.

It’s possible that impeccable design logic, you learnt at that architecture school, may be preventing you from pursuing your design research to its maximum limit. As suggested above, Design logic may actually impede you and tie you up in critical negative knots to the point where you are unable to do anything.

You may just be re-problematizing the same problems. Or worse still, just trying to impress the underlings in your studio.

- Speculate

- Do a competition.

- Target an area of interest and design a theoretical project.

- Design something totally wacky.

- Try and design a crap project.

- Find a weird location or site and propose something for it.

- Invent a new building type. Or at least try to.

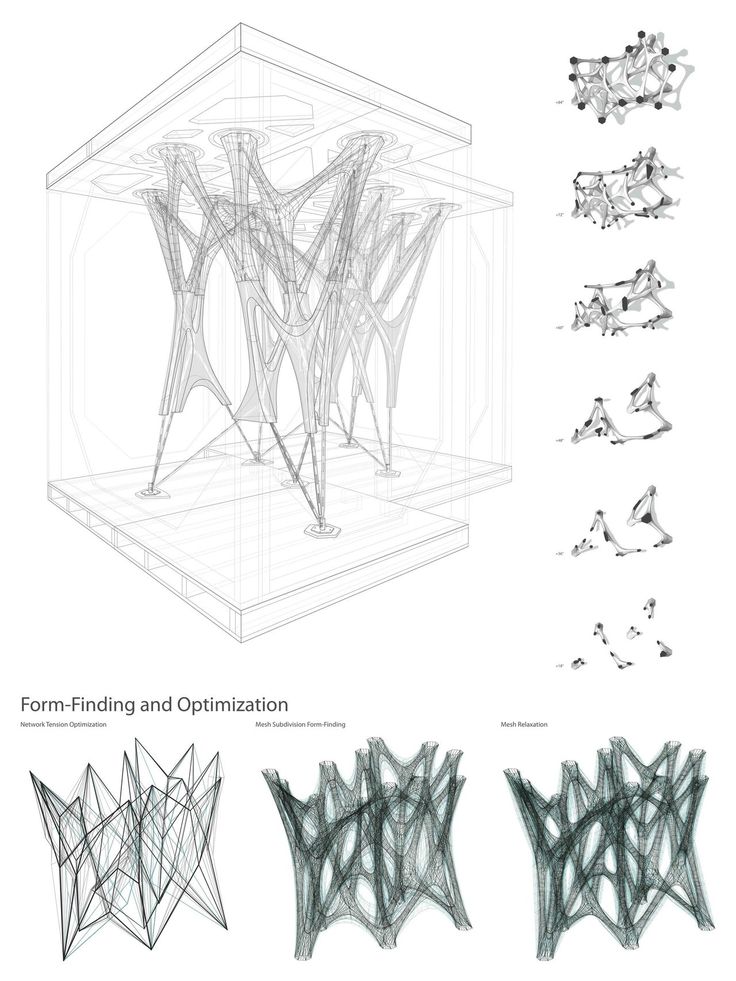

- Deliberately screw up that parametric model.

Paradoxically, pursuing design failure means that architects will fail less. It means we are pushing back, testing the limits and boundaries of our discipline. It might give your practice an edge in the future. It means that the design knowledge we produce is not simply packaged up and then commoditized. Instead it is knowledge whose limits and effectiveness has been tested with the blow torch of failure.