Archigram and Anxiety

I am pretty busy this week (conference paper writing) and mid-semester crits are looming at my graduate architecture school on the periphery of the global architectural system. So I thought it timely to republish this blog from last year.

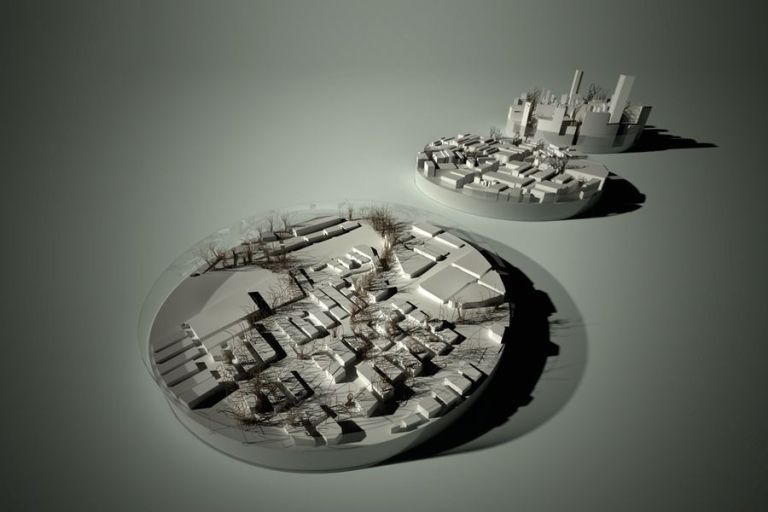

The above Archigram image is mean to soothe even the most anxious architecture student.In fact whenever I get tense or uptight about architecture I pop out, have a cup of tea, and look at a bit of Archigram. They were a pretty relaxed bunch of dudes. (doods being the operative word). In fact Peter Cook’s recent exhibition at the Bartlett has just closed last week celebrating his 80th. Rumour has it that somewhere in the archive of the 1960s there is a picture of PC in a kind of Emma Peel Avengers style PVC jumpsuit. I would give my back teeth to see that and it would it would make a great paper on taste-making and gender in the architecture of the 1960s. Of course such a paper would have to discuss Reyner Banham’s rants about Jane Fonda in the Barbarella film. There is a it about it here. Maybe those smart-arse and well funded researchers at Princeton should examine this stuff.

Cookie and the other GUYS in Archigram never really got too anxious as they were all to busy playing footsies with the girls under the table, drinking tea, and smoking huge spliffs. Not surprising that the girls in the back row never really made the club.

Looking at Archigram projects, and following in their anxiety reducing practices, may be one way to cure anxiety. But Anxiety is one of the most debilitating things that can beset you prior to the design jury or a crit. It’s hard enough being an architecture student. No money, long hours, and the struggle to learn a complex discipline. Pre-design crit anxiety can be crippling. It can certainly stop you from working effectively and it can prevent you from communicating your ideas and what you have done effectively in the actual crit. You are not alone almost every architect or architecture student has had to face this anxiety.

The Looming Deadline

Of course, it is worse if you are approaching a project deadline or the end of semester. It is worse if you do not think that your tutors, or the client group, or a consultant, is not on your side. It is also worse if you feel that maybe you haven’t done enough work and it is even worse when you are earnestly struggling to build your skills, design confidence and resilience.

I am writing this from a number of perspectives. Firstly, as someone who knows what it is like to be anxious about a studio crit or a meeting. But also as someone who is on the other side as a critic who has seen the anxiety of architects and architecture students. As a young design tutor straight out of my cultish architecture school I was a somewhat fierce and unreasonable critic who developed a reputation for making students cry and jumping on models. Thankfully, after 30 years those people have forgiven me and I now realise how reprehensible and disgusting my earlier behaviour was.

There are of course a number of things you can do to manage the situation and manage your anxiety before that terrifying crit or design jury. Here are my suggestions:

Sympton 1: Thinking the worst

Your imagination can run wild, you can think that the worst will happen. You will be cut down by other architects, the client or jury members, and you will be humiliated amongst your peers. I suffered from this and it can be debilitating. Don’t replay in your imagination the worst things that people might say to you.

Cure: Remembering most critics are interested and want to help.

Thinking that the worst can happen is never good. I have been in and seen some pretty bad crits in my life. But, nowadays days these are extremely rare. Most design jurors and critter people in the 21st century are a pretty decent lot. Find out from your tutor who they are and do a bit of research. Usually, they are attending because they are either a convenient friend of your tutor or they have some kind of special expertise that is relevant to the studio.

They will probably not tell you that your work is appalling or rip the prints of the wall or jump on your model. It is unlikely they will belittle you or humiliate you.

They will tell you what they think and usually they try to be honest. Mostly, they will be interested in what you have done.

If you feel anxious before the crit try imaging the sort of interesting questions they might ask you. Make a plan for what you will do before the crit and what you will say. Don’t just turn up and wing it. Be prepared. Making a plan of what you will say and even practicing it in front of a mirror before hand will help you minimise your own anxieties. In other words, imagine them asking you the questions you want them to ask. Imagine the crit going well rehearse what you a going to say using this formula set out in my previous blog.

Symptom 2: Over work anxiety,

Anxiety feeds off overwork. Not enough fun or enough rest will fuel it. After my own architecture thesis I went camping on a river and just sat in a camp chair for about ten days and did not move. I was so burnt out from overwork. This can happen to anyone no matter how old you are. I have known student’s who haven’t stopped working hard since high school. At some point they discover they need a break because they are really burnt out.

Working all night will fuel pre-crit anxiety. Not getting enough exercise will make you more anxious. Or just have a rest or go out and play with your friends. There is no point working and working and working and getting so tired. If you are tired before the crit your anxiety will be harder to manage.

Cure: Have fun and get balanced.

If it gets really bad go for a walk. Go to the pub. Go shopping. Go out with friends. Sometime you can overdose, and burnout, on a design project or a studio or even a course. Read this.

Be mindful, try meditating, there are some really good apps you can get that will lead you through some great mindfulness exercises.

Symptom 3: The best friend of Anxiety is procrastination.

I might have said this here before on this blog, but procrastinating, by deferring the activity of design and design gestures, will only make your anxiety worse. Designing is a labour intensive exercise (especially if you are using a computer). Putting it off only means you have to do the same amount of work in less time. Designs are not made and fully formed in the brain and then exactly transferred to the computer or paper or the physical model. If only we could do this life would be so much easier. Designing takes time.

Cure: Work constantly.

Reading, researching, writing little notes, thinking while drinking that batch brew or Aero press coffee, going to the fridge and eating, web surfing and Google searching are all the fabulous ways to defer the actual act of designing. The problem is designing is about either physical or digital drawing and the sooner you start the better. You will be less stressed if you work constantly throughout the studio and avoid procrastination. If you do feel stuck get help or advice from your tutor to get unstuck.

Symptom 4: The other people are always better

There will always be someone in your studio who seems better, smarter, more creative and more like one of those over-confident alpha-male architects. Thinking this is real recipe for anxiety. You will always be your own worst critic and these other people will always seem better. I mean who needs design tutors or guest critics when you are so good at demolishing your own design thinking and ideas?

Cure: Run your own design race.

It’s best to solve your own problems rather blaming others or being focused on your fellow studio members. Run your own race. Believe me you will actually end up doing better. Focusing and comparing yourself to others is waste of energy. They will always seem better and if you think like this your anxiety will easily be fuelled.

Symptom 5: Critical negativity

Also, don’t compete against yourself. Know when to give yourself a break and when to be critical of your own judgements. Too often I see students tied up in knots and paralysed by their own critical negativity. As designers we need to question. But we don’t need to question every single tiny thing related to a building design. The worse architecture schools on the planet are the ones who promote this kind of claptrap critical negative method.

Cure: Remember there are no right answers

Sometimes it’s often better to design something, anything really, even if you think it might be “wrong”. The alternative is always to be searching for the “right” or correct idea and that is an ideal that doesn’t exist. Or after you have developed an idea for a while in your design its thrown it out and everything else with it. Because it is not correct. I see a lot of this. To develop design confidence and resilience you need practice in developing a design.

Symptom 6: Don’t kick the cat; or anyone else for that matter.

This is a rare, but not uncommon, symptom of anxious students. People and indeed architects under pressure who get extremely anxious sometimes release that pressure by lashing out at their pets or others. Please don’t kick your dog or cat when you get anxious about the upcoming crit. It is also really good idea to not lash out or blame your tutor, or your fellow classmates, for your anxiety. Usually your design tutor is trying their best to guide you and get you through.

Also, speaking from experience, your tutor will not think highly of you if you do this. I am usually relatively understanding if someone lashes out at me when they are under pressure during the studio. There is not a lot I can do when it happens. But, as a tutor it is not pleasant and usually it means that after the studio is finished I don’t really want to have much to do with the lasher-outer type.

Cure: Don’t bottle things up and build ongoing relationships.

Instead of lashing out talk to your tutors and your peers about your fears and anxieties. You might find everyone, tutors included, are just as worried as you are. Try and remember that after the studio has finished the most important thing you can do as an architecture student is to retain and have a continuing relationship with your peers and those who have taught you as an architect. Each studio is an opportunity to build your future professional networks.

Symptom 7: So maybe you haven’t done a lot of work and that’s why you are anxious.

Yep. You realise there is only two weeks left in the studio and the deadline is looming. You are definitely going down the tubes because you did not do enough work earlier in the semester. You are running out of time. You have been too busy having fun or you haven’t really been thinking about the time. You are not sure how you are going to actually get everything done. Even if you work all day and all night you think that you are going to fail.

Cure: Get help

Symptom 7, along with just about everything symptom above, is best cured by getting help.

Tell your tutor your predicament. Most tutors will be sympathetic. Most tutors want you to pass and even if they recognise that you have done no work they will still help you. But to do that you need to get their help and you need to be honest and realistic about what you need to do. Talk to your friends try to enlist their help as well.

Finally

If of course your anxiety is becoming to much of a burden you may need to get help from a counsellor or your GP. Most universities and architecture schools have avenues and contacts that can help you overcome anxiety. Sometimes the worst thing you can do is to think you can just push through and ride out the anxiety. It’s a lot easier if you always get help and remember that you are not invincible. The most important thing to remember is that you are not the only one to ever feel anxiety prior to a design crit.

It could always be worse imagine if it was Cookie and his crew you had to present to.