Season Greetings

Of course, getting this close to Christmas its time to thank everyone who has actually bothered to read this blog. Thank you so much.

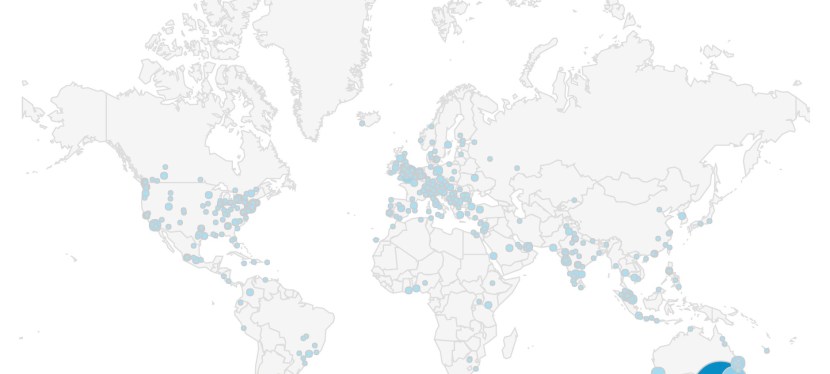

The blog has gone from strength to strength this year and the number of unique visitors has doubled. Whilst the blog has primarily an Australian focus there are still many visitors to it from elsewhere. The largest number of visitors outside of Australia are from the USA, Europe and India. Many people visit from the cities of London, Mumbai, Los Angeles and even KL. Architecture is indeed a global system and one aim of the blog is to explore the inequities, contradictions and limits of this system. Of course along the way it is hoped the blog can help architects learn how to navigate their way around the design studio.

Next year the look of the blog will get a makeover and I am hoping to get some podcasts interviews with architects up as soon as I figure out how to do that over the summer. In the meantime thank you for all of you who regularly read Surviving the Design Studio. I will of course still be transmitting over the Southern hemisphere summer.

The @archienemy awards for the 2017

There has been a lot of talk about architectural urban and architectural ugliness in the media lately. It’s easy to blame the architect for “ugliness”, whenever anything is outside of a “stylistic” norm; yet, that norm is never defined. As an invective ugliness has had some measure of success in the media and continues to do so. I hate it when the political class, usually unversed or untrained in visual arts, decries something as ugly. More and more it’s becoming a way to grab media headlines. Perhaps there has always been an anti-intellectual streak towards architecture and the visual arts in Australian public life. Architects need to call this tendency out at every opportunity as it has coarsened our public debate around what our civic realm should be like.

As an architect recently pointed out to me recently the use of the term ugliness by politicians, contractors or property developers and the like is usually accompanied by an underlying or concealed economic imperative. My favorite example is Southern Cross Station whose procurement and delivery was mismanaged by the contractor after a very low bid for the project. Of course, the large contractor got mileage in the press complaining that all the problems were the result of the “krazy roof” by Grimshaw Architects. The roof is great. Earlier in the 2000s Federation Square was no different at the time of its construction. LAB’s great Western Shard at Federation Square was zilched, by a coalition of contractors, politicians and the tabloid press in 2002. Easier to blame the architect every time. Of course Federation Square has come to be a great civic space in the city.

So here are my top 5 @archienemy “ugly” awards for 2017. These are examples of the real ugliness underlying our architectural and urban discourse. Architectural aesthetics is entwined with politics and to think otherwise is a mistaken conception.

Of course I would be happy to get further nominations for next year, or even late nominations for this year. Don’t hesitate to let me know.

1. Ugly Office Makeover Award: 222 Exhibition Street

For some reason this addition really annoyed my sensibilities. Probably because it is indicative of a situation that is all too common. It has been given a kind of fake and folksy parametric make over by Jones Lang Lasalle. So they get the award. No idea if there is an architect. The casual and unthinking destruction of a fine Post Modern building originally designed by DCM.

Apparently all this flummery is in the name of sustainability ratings. I wont call the new additions a dog, but I think the slightly lesser rating of shocker, is relevant. This sort of thing only reinforces my prejudice that sustainability consultants, despite their hyperbole, have no regard for aesthetics and that the sustainability push in the context of commercial office space is so often greenwash.

The original building, 222 Exhibition Street received a RAIA Merit Award New Commercial for DCM in 1989.

2. Ugly Security Addition Award: Parliament House Fence Canberra

The Parliament House fence. Not sure who deserves this award. Maybe the AIA for going along with it. It should have been an Australian wide design competition. But that would require political leadership. It was simply a bit of a media debate and a process focused on security. A debate that, as it progressed, at no point questioned the aesthetic or symbolic implications of putting a fence around Parliament house. I met a journo who works there and mentioned it to her. She didn’t really get it. Who cares about that stuff when our secure lives are at stake. The fence says, its ok if we look like a Gulag state as long as we are safe.

I know it may sound crazy, but I think there is a logic in the idea that we are now living in our own Australian version of Stalinist style social realism. Soviet social realism existed in order to generate and transmit propaganda from the ruling class into populist mythology. Is this any different?

No.3 Its Brutalist so its Ugly Award: The Sirius Building

The actual award goes to NSW Treasurer Dominic Perrottet who unleashed a vitriolic diatribe via the Daily Telegraph on 28 July, dismissing the Sirius building as “a boxy blight on The Rocks,” made from “towering slabs of grimy concrete,” that stands as a “drab relic of union power.” He went on to say:

Comments like that seem to bear a lot in common with the celebrity fascist Milo Yiannopoulos comments about the Opera House here. Actually you have to Google the link yourself. I don’t actually want to give Milo much air. Again, you have to ask are we living in our own version of Soviet Social Realism?

As noted in a previous blog this award pretty much sum’s up many of the battles over state-owned land in our cities. The NSW government seems determined to sell the site. Why not make it an international architectural design competition? Rather than some low-grade property investment tender orchestrated by people who look like they come out of the Riviera series.

Of course we all know, the money made from any Sirius sale will not go back into social housing. It will just dissipate in treasury accounts and be used to rebuild a few new ageing stadiums. After all the sporting brands are worth more to the state than the social housing brands.

4. Apartment Clusterfuck Award: Ministerial Planning Approvals.

I don’t normally like to sound overtly partisan, but we are now witnessing in our city the results of Matthew Guy’s planning decisions, from his time as planning minister between 2 December 2010 – 4 December 2014. There is always a 2 to 3 year time lag with tower builds. If you are in Melbourne just go down to the corner of Franklin street and Elizabeth street and have a look around. You can follow the links below in Google street view. You will wonder WTF happened? Well Matthew Guy happened and the award goes to him.

Super Tuesday 2014 and also in June 2014 was Guy’s best of times. But follow the link below to see the resultant cluster of apartments.

5. The Apartment Ugly Standards Award: Plus Architecture

Its great when architects lobby politicians to make the world a better place. There is nothing wrong with that. It is always good to see actual architects engaging with the political sphere. This award goes to the fine firm of Plus Architecture. In particular to Craig Yelland. Plus is responsible for some truly great projects around the city.

Richard Wynne the planning minister who succeeded Matthew Guy actually put in place a policy to mitigate the worst of the apartment plans in Melbourne. The policy can be found here and the standards came into place in April 2017.

I really enjoyed reading the counter arguments from Plus Architecture about how much extra these minor changes were going to cost the so called consumer per apartment.

It seems they were going to cost the consumer, and developers, of these apartment products a lot of money. But sadly, no thought in the analysis by Plus to the longer term costs or benefits to the community or the city.

Finally

If anything, the above awards indicate the continuing power of the property development lobby. Whole of life costs are usually missing in action. Cowboy aesthetics often reign supreme. Riding shot gun with the developers means just making those priapic towers bigger and taller and meaner inside. Its a lobby that arguably has no interest in urban aesthetics, amenity or the quality of civic and public spaces. Its a lobby more interested in the comforts of its seaside beach house taste culture.

Combine the developers with unthinking provincial politicians and its little wonder our cities are degrading almost as soon as they are built. Of course, it is always good to see actual architects engaging with the nexus of property development issues and politics. We definitely need to have the debates around “ugliness” when the ignorant impinge onto our disciplinary turf. But some architects also need to ask whose side are they actually on?

Daphnes Spanos Autonomous Waypoint project from Independent Thesis MSD 2016

Daphnes Spanos Autonomous Waypoint project from Independent Thesis MSD 2016