The image on the home page next to this post is a picture of a typical architectural researchers desk. Sadly there are people in this world who dont think architecture has much to do with research. Even I sometimes have trouble convincing people that I am actually doing research.

Yet, in recent practice, architects have argued that architectural design is a research activity in its own right. The research activities of architects include a range of problem solving and design related research activities such as data collection, workshops, internet searching and design drawing. In addition architects also research historic precedents, climatic issues, construction methods, products and materials. Design as research, also points to the emergence of research amongst architects related to the scripting of programmes, 3D digital modelling and prototyping. But is design research simply speculative or generative designing?

I like many other architects agree with the proposition that designing can be research. But this is clearly a problematic proposition.

The design as research culture

Numerous PhDs, design studios, books and even entire courses have been built around the notion of Design as Research. In fact no one really knows how to write it: design research, or is it Design Research, or is it “design as research” ? But the real point is that, many architects regard design processes such as creating sketches, making digital CAD models, building physical models and building prototypes as research. But is that what design research is?

Of course, some have had a go at defining what it is. Dr. Peter Downton at RMIT argued that design is a ‘way of enquiring a way of producing knowledge; this means it is a way of researching.’ In a study of architectural design PhDs Radu asserts: ‘Architectural design is to architecture what research is to science’ and the ‘process of architectural design is close to the process of knowledge creation in the sciences’

No research infrastructure

Across the globe system there is clearly a lack of research infrastructure for architects at a number of levels; research infrastructure doesn’t just mean having big grunty boyo computers. In my country of Australia, research skills are not clearly articulated in the architectural accreditation system. Architects don’t often do formal research methods courses and few graduate schools of architecture offer courses around design research. Notably, my own school does offer such a course. Worse still design research outputs, such as buildings are not counted in research evaluation and publication exercises.

The reality of practice.

In actual practice, I fear that the documentary, formal and methodological structures supporting the organic activities of design research are fragmentary and adhoc. Few practices have formal R&D procedures in place, and few practices have developed procedures for articulating and documenting its original design outcomes. Aside from, practices publishing their projects for peers and marketing. much of the knowledge generated by all of the research in architectural offices remains largely implicit within firms.

Few firms write research reports on the information they collect and yet many often claim that research information is transferred to other projects. These adhoc practices make it difficult to ascertain, and argue, which aspects of architectural research are a contribution to new knowledge.

Research models in practice

As a result, many firms flounder around when it comes to research. A lot have tied their own research models focused around digital design and fabrication. Other firms have focused their research on Sustainability. But simply having and seeming to follow through on this research focus is not enough. A few firms go beyond a simple focus on a strategic research area. Many dream of, or attempt to adopt, research models related to a management consulting. Larger firms are better at this. But this is, more often than not, without the well-worn and templates and proprietary methods that real management consultants have.

Moreover, only a few architects have embraced research models related to patent innovation and product development. I am still struggling to teach graduate archi students what Intellectual Property is.

The research paradox for architects.

The paradox is that many architects often state that research is a part of their design philosophy yet there is often no further articulation of this. Often in practice the organic integration of routine research and design as research activities makes it difficult to identify what is routine design and what is design which creates new knowledge. Establishing the contribution to knowledge of any research endeavour is necessary if it is to be regarded by non-architects as research. I worry that to many architects in practice R&D is about simply placing product and materials information at the back of a project file.

This is not to say that architects do not develop new knowledge or insights as a result of design processes. But, many firms appear to lack the methodological infrastructure, systems or research training needed to support R&D activities. This makes it difficult to isolate and position the research knowledge and innovations arising out of design research. Without these methodological and meta-structures in place it is difficult for architects to argue how design as research makes a contribution to knowledge. It also makes it difficult to position and distinguish new design from previous design research.

Policy failures

The focus on design as research, and its rise in architectural schools, has too often tended to emphasise research related to material issues: drawing, modelling, fabricating and constructing. But further research in the architectural schools could identify to what degree design as research in practices is focused on non-material and context-dependent topics: urban space, gender identities, teamwork, and cross cultural issues. Not to mention history and culture.

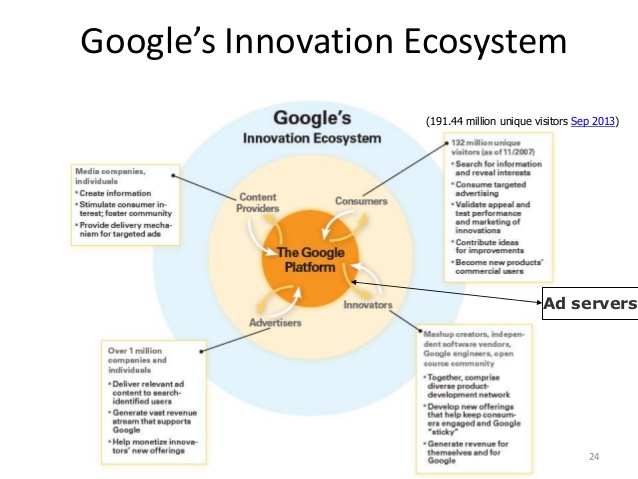

Arguably, few other professionals would actively have this broad range of skills and expertise at their disposal. Yet, the role of architects is not often accounted for or encouraged in national innovation systems or construction innovation policies.

All the politicians love a so-called smart and sustainable city. We require initiatives need to examine in the potential role of architectural design as research in national innovation systems. These considerations could lead to policies that highlight the linkages between, design as research arising out of architecture and new technologies, construction, industrial design and manufacturing. But at present the design thinking and research of architects is often subsumed and only seen as a minor element in national innovation, research and educational policies. As architects, we need to build and develop our industry in a way that substantiate, explore and promote the design research agenda to the max.

Just designing, and then making something, and then claiming that this is research will not be enough.

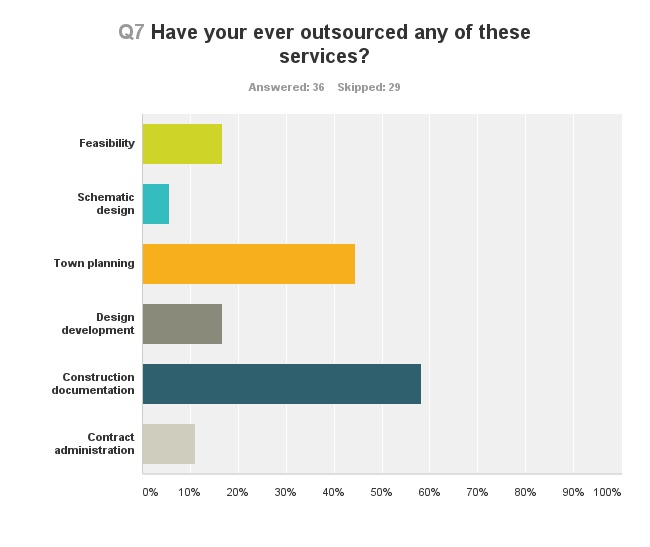

Chart 1: Outsourcing is widespread

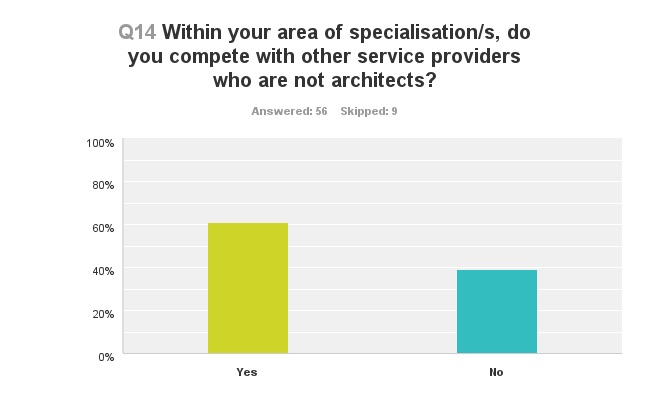

Chart 1: Outsourcing is widespread  Chart 2: Competition is Intense

Chart 2: Competition is Intense