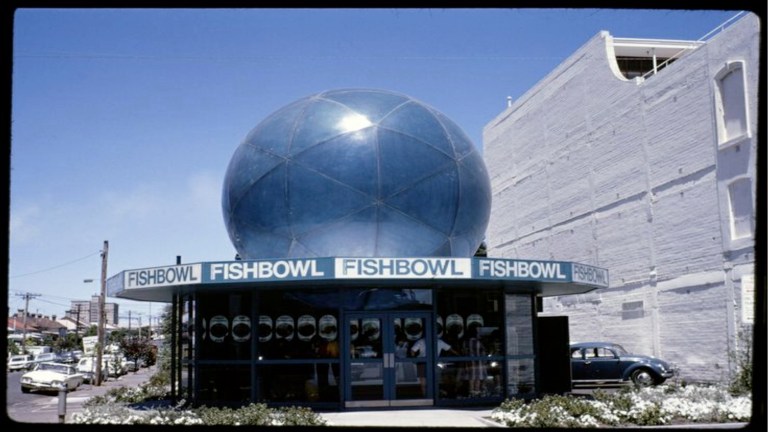

A few years back I was invited to do a poster, so I made a kind of comic which I then turned into a larger collaged piece within a frame. Given my total, and in some ways perverse, avoidance of digital skills I have always been more comfortable creating with photocopied images from books using crude collage techniques. My brain is a library of all the images and memories of architecture I have consumed in life. Some of these are in the Gloop narrative.

When I produced the Gloop collage it had been quite some time since I had actually done anything creative. This was because in some ways being creative was beaten out of me at architecture school. Firstly, I wasn’t good looking or charming or genteel enough to get a High Distinction for my architecture thesis. The High Distinction in my year went to the taller, good looking architect, who then went to the east coast graduate school. I was pretty annoyed that my tutors gave him an extra two weeks to do his work. Arguably, my special brand of thesis craziness, evidence by my drawings, was never going to get the big mark. But nonetheless, it certainly wasn’t a level playing field and that is probably why to this day I feel that studio jury and moderation processes in architecture schools need to be absolutely transparent and fair. The masculine clubs, networks and pedigrees that seem to confer design authority on some and not others has always repulsed me.

Architecture Thesis 1986: Federal Court of Australia

When I did my Masters of Design after my Bachelor of Architecture I tried to design a few things but was beaten down by the tutors whose idea of architecture was so precious, and dare I say it anal, that every fucking line had to be argued and justified. I certainly didn’t think that designing was about drawing the same line over and over again, until you break out into a sweat, and then finally, and inexorably, draw an oblique line; or get some banal insight into a typological context or history that propels you to draw more of the same lines again. Or worse still, draw the lines over and over again, waiting around for some second-rate “Master” or auteur to tell you what to do when they get back from the client meeting.

Even when I was in practice there were only a few things I felt I had actually designed. Mostly, these were competitions which were always won by the usual suspects, and lists of big networked firms, who had lots of infrastructure and staff. Everyone else seemed to win these except for our practice. Well thats how it felt at the time. We did about four or five competitions over about 2 years and no-one who mattered really took much notice. Doing these competitions killed the practice because of the resources they depleted.

None of our competitions were published and I had to grovel to get a sessional teaching job from the local overseas implanted head of the architecture school. The comic aesthetic didn’t really help. Nor, did it help that we weren’t in the boys club of that time. I drove cabs and my partner did planning gigs. Although, during this time in practice I did manage to design one thing that still exists today and I was relatively happy with. Even though the client wanted to sue me. After a while I ended up leaving architecture. I was so sick of it and the lack of opportunity and generosity and the clubbiness.

Nowadays, I really think we, all of us in the cult and discourse architecture, need to encourage small practices and emerging architects. We need more competitions, we need more enlightened larger clients who take risks with smaller practices and we need larger firms to mentor smaller firms. We need more mentoring and authentic career pathways in architecture. We need professional associations that actively foster and mentor small young practices. We need more inclusiveness. We need exhibitions that show what emerging prcatices are doing. We need to save and archive the outputs of the studios led by young and emerging architects. We need to look after each other.

By the time I did the Gloop collage I had come back to the fold of architecture. It was probably the first creative thing that I had done for many years. I did the collage in the space of two days. The collage and the images quickly came tumbling out. In my conceit, I felt like Ranier Maria Rilke at Dunio near Trieste when he wrote Duino Elegies, after not writing any poetry for a long time. Maybe, I should change my name to, or name my next child, Rilke Raisbeck.

But the real point of this is that it doesn’t matter how unksilled or messy we feel we might be as architects. As architects, we are all struggling in systems, or contexts, that do not seem to value our efforts. Despite my bloggy cynicisms, I think that even when we are unable to design or build, or we lose the competitions, or we go bankrupt, or the clients want to sue us, or we are discriminated against, we should never let go of our own ideas or sacrifice our continued learning and development as architects.

I hope you enjoy the story of the Gloop.