In this week’s blog I resuscitate from my vault an old conference paper which discusses design processes. This came after a conversation with friend about how and why his firm of architects is suffering because they have not won a lot of new work recently. I think this blog might help those architects and other creative orientated firms, stuck in a rut, and seeking to reflect on their creative processes.

The BIG IDEA syndrome

Trump is full of big ideas like build a wall, lock up HRC and even all those franchising ideas Trump steak, Trump uni, Trump perfume and Trump Vodka. Sadly for some there is a view that creativity and genius is something innate. A secret sauce or recipe that is embedded in our DNA. This sensibility leads to people looking for the one big idea. The BIG IDEA. Dare I say it: the big fucking idea. The secret to the universe or the solution to the particular problem. (Of course as noted in another blog when the problem is “wicked” there may not even be a single solution). Unfortunately, in the many professional cultures, for example architecture, urban design, landscape urbanism and maybe even advertising, the single idea or big idea view reigns supreme. Once you have that idea you, or the team, runs with it. But as Andy Warhol said of Trump he is kind of cheap and I think the same about the Big Idea in architecture. It’s always kind of cheap.

So, what if the one BIG Trumpian idea is crap? How do you avoid the Bad BIG IDEA syndrome (it’s a bit like saying how can America avoid Trump)? If the idea is bad you might lose the competition, the job, the client or the pitch. You might even lose the confidence of your team working on it. You might end up with a design or an end strategy that is so bad that all you can do is polish it a bit (there is a saying for this but I think I can only sustain one profanity per blog post).

Paradoxical Design can save you

One way to get around this conundrum is to abandon the focus on the one big idea syndrome and always build a portfolio of ideas into your design practice. This is done by deliberately fostering the generation of paradoxical or counter ideas in a project. Ideas that are in opposition to the prevailing project idea. In opposition to the one BIG IDEA. In other words, its great have a few paradoxical, counter or oppositional ideas being pursued at once. Yes, it makes for chaos with contradictory ideas are competing at some point in the project but this is manageable and ensures that you are not locked into a dog of an idea. The counter ideas can help you to test and compare the prevailing idea. Not only that but you can use the paradoxical ideas in other projects in the future.

Design thinking is about constantly generating creative ideas and every project should run with and explore a few ideas in parallel. This is one aspect of design thinking that most, but not all architects, understand and are taught in architecture schools (well some of the time anyway).

Running with a few paradoxical ideas might actually save time and effort (and of course money) in the long run. The problem is that for architects or other creative design professionals changes are often seen as being unwelcome and at odds with sequential project development milestones. Changes are often seen as negative in a productivity sense; or changes contribute to rework during the construction or production process and this adds costs to project risks. Also, there is the perennial problem of how you explain changes to the client.

But, on the other hand creative and generative design is seen to foster innovation and this is at the heart of the design paradox. One way is to ignore this constant paradox but the other way is to embrace Paradoxical Design.

Paradoxical Design and innovation

In innovation theory a number of notable theorists also suggest that embracing Paradoxical Design means recognising, but also fighting against linear and binary descriptions of the design process. As Winch theorised (sorry to get all academic here) designing can either be characterized as either a conjectural model or a linear model (Winch, 1998). He argues that the linear model is a problem solving approach which involves analysis, synthesis and evaluation. Which is all very well and dandy. But he goes onto argue that the conjectural model, a model which is arguably linked to ker-razzy assed architectural design, is more discontinuous or disruptive. For those of you reading this interested in innovation theories and systems, in Clayton Christensen’s parlance, (the elder-king of innovation academics) conjectural design is what might be termed as exploratory innovation.

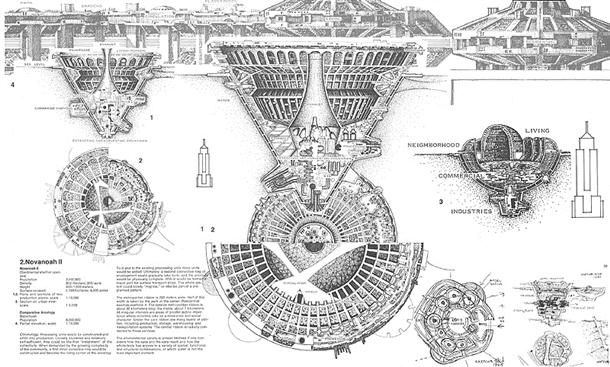

In Paradoxical Design, an initial hunch or conjecture is formulated and following this the process then proceeds through a number of iterations. It is through these paradoxical iterations that design knowledge is created; in each iteration conjectures are proposed and then abandoned. The iterations, or the creative idea embodied in each one, are paradoxical because they might be quite different to one another. They may even contradict each other.

A rapid survey of architects

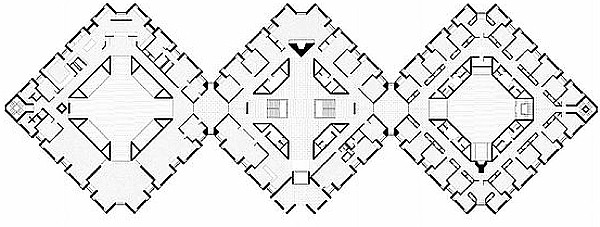

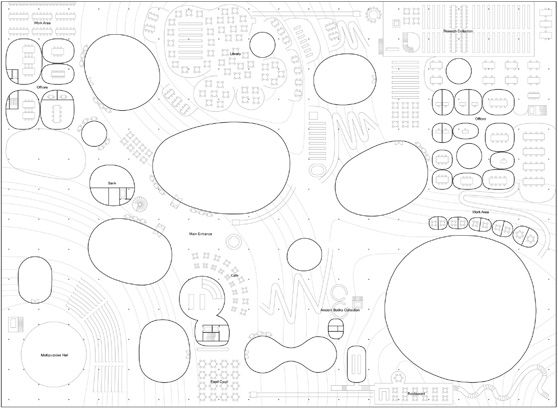

In a rapid survey I did a few years back of architectural firms practices in Australia in a desperate effort to churn out a quick conference paper. I aimed to find out to what degree architects pursue Radical Design vs Incremental Design solutions as design projects progressed. You can find the paper here. Its full of diagrams describing the process I am describing.

To cut a long story short, in the survey I defined Radical Design solutions as: solutions “leading to fundamental rethinking of elements of the project”, “affect the form or conceptual origin”, “change the design concept” or “a change that affects the fundamental design – so great that the concept must be re-assessed or thrown out.”

In the survey which had about 70 respondents the term Incremental Design was seen as being “stepwise improvements” or “incremental refinements of an existing idea.” Incremental Design represents linear, logical, and rational design gestures and solutions.

Survey results

28% of the Architects surveyed responded by saying that “Pursuing radical design changes is a part of the practice’s normal design process.” 29% claimed that “In our practice any project the principal designer, designer teams and design architects have the time to pursue new design solutions throughout the project.” More importantly. 42% stated that “continuing to generate both Incremental and Radical design solutions throughout the process helps to identify and highlight new design issues and problems as the design progresses.”

In terms of cost benefits, 21% responded that “Continuing to generate both Radical and Incremental design solutions throughout the process outweighs impacts on project delivery time or cost.” But despite this 72% acknowledged that sometimes it is necessary to discard a design solution or sketch design and start the design process again in order to achieve a better project outcome. And 65% agreed that “Creating and then culling both Radical and Incremental successive design solutions in a given project helps to achieve high quality and innovative design.”

Design architects are often accused of changing their minds once decisions have been made during the project development and delivery process. Some see this as architects just being all about ker-razzy assed architects. For other professions, even creative ones, paradoxical design is not possible. This is because an investment in design itself is seen as all too costly and wasteful. Let alone running with the wolves of Paradoxical Design. But, on my town we all remember the brouhaha over Federation Square; which turned out great despite the village naysayers decrying its cost and design.Of course it is always cheaper to run with one idea. But, a badly and cheaply designed building or project has many longer term societal costs.

But if you really want to find the creative idea that is so compelling that clients, users and the punters can’t resist it then you are not going to find it just latching onto the first big idea that comes along. Thats part of the paradox I guess. You may only get there by thinking about a set of pradoxical ideas rather than one BIG IDEA. In any case, thinking about and managing Paradoxical Design processes is a great way to build design knowledge and a portfolio of design ideas in your firm. Paradoxical Design thinking is essential to winning those clients, the big commissions and the awards.

My students in the colliding spaces studio have pretty much finished the semester. thankfully no one imploded. A few even seemed to enjoy it ! But then again as we all know archi-students will say a lot of nice things about their tutors to get a good mark. I am hoping to put their projects up on this site in the next few weeks.

Stairs are always a place of apprehension and darkness; often the back stairs are where the budget ran out or where the fire services are fully revealed or where you may never encounter others. In the Switch House stair system this a generosity of space, attention to material detail, views to the exterior, as well as view lines along and across the vertical circulation spaces to other adjoining spaces. There are a series of different promenades within the building, through the undercrofted old tank spaces, the heroic helical stair, vertical stairs, and outside the lifts and along the perimeter walls with glimpses of the outside world. This is a hollowed out pyramid with a palimpsest of interior spaces. In this theatre of spaces the silhouettes of both individuals and small groups seem momentarily freeze framed before they move on.

Stairs are always a place of apprehension and darkness; often the back stairs are where the budget ran out or where the fire services are fully revealed or where you may never encounter others. In the Switch House stair system this a generosity of space, attention to material detail, views to the exterior, as well as view lines along and across the vertical circulation spaces to other adjoining spaces. There are a series of different promenades within the building, through the undercrofted old tank spaces, the heroic helical stair, vertical stairs, and outside the lifts and along the perimeter walls with glimpses of the outside world. This is a hollowed out pyramid with a palimpsest of interior spaces. In this theatre of spaces the silhouettes of both individuals and small groups seem momentarily freeze framed before they move on. In some ways the antithesis of the Tate Modern’s turbine hall and galleries. In these one is subsumed by the monumental spaces of a now archaic industrial technology of

In some ways the antithesis of the Tate Modern’s turbine hall and galleries. In these one is subsumed by the monumental spaces of a now archaic industrial technology of  The Switch House is certainly more claustrophobic than the spaces of the turbine hall and there is a dissonance in the architecture with its odd juxtaposition of concrete columns, brick lattice grill work, and seemingly adhoc spaces which come into much closer confines with ones body. This is not a public palace that one can walk through easily as a god-like citizen of Rome or Athens, ala Richard Meier at the

The Switch House is certainly more claustrophobic than the spaces of the turbine hall and there is a dissonance in the architecture with its odd juxtaposition of concrete columns, brick lattice grill work, and seemingly adhoc spaces which come into much closer confines with ones body. This is not a public palace that one can walk through easily as a god-like citizen of Rome or Athens, ala Richard Meier at the  My own biases makes me think that the extension points to the architecture of Loos, the paintings of De Chirico or the subtle yet weird surrealism of

My own biases makes me think that the extension points to the architecture of Loos, the paintings of De Chirico or the subtle yet weird surrealism of  There is a real treat on the viewing deck. The viewing deck is great because you get a 360 degree view of the City. The sense that you are in a public building is further emphasised by the fact that you can see directly into the neighbours houses in the unfortunate

There is a real treat on the viewing deck. The viewing deck is great because you get a 360 degree view of the City. The sense that you are in a public building is further emphasised by the fact that you can see directly into the neighbours houses in the unfortunate