For regular readers of this blog, I am sorry for going AWOL for a few weeks. This is the biggest break from my weekly blogging that I have had since I started this endeavour. Of course, I feel a little guilty. But hey, this blog is not always about the Google stats, if it ever was. For the past few weeks, I have been in Italy and managed to visit the Architecture Biennale. So, dear blog reader the next few blogs will focus on the 2018 Biennale. So dear readers, you can now say, as they say in the Chucky Movie he’s back. Typos and all.

Freespace

Freespace is the theme for the 2018 Architecture Biennale, and it has been curated by two Irish architects, Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara. It is thought-provoking and well curated, and this is the best Biennale I have seen. They have done a great job. And for the most jaded of architectural hacks such as myself, looking at it through a haze of Cocchi Americano spritz, the curators have presented their theme as a comprehensive vision (Aperol is no longer my drink of choice on the lagoon). Its a vision of what architecture can aspire to be. Compared to past Biennale’s, it is not as muddled as Chipperfield’s theme of “Common Ground” or as ambiguous as Sejima’s “People Meet in Architecture” of 2010. This Biennale, unlike previous versions, has its very own manifesto written around the notion of Freespace.

The Manifesto

Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara are graduates of University College Dublin and their practice is called Grafton architects . The Freespace manifesto has six points. You can read the entire manifesto here. Here are a two manifesto points for your edification.

FREESPACE can be a space for opportunity, a democratic space, un-programmed and free for uses not yet conceived. There is an exchange between people and buildings that happens, even if not intended or designed, so buildings themselves find ways of sharing and engaging with people over time, long after the architect has left the scene. Architecture has an active as well as a passive life.

FREESPACE encompasses freedom to imagine, the free space of time and memory, binding past, present and future together, building on inherited cultural layers, weaving the archaic with the contemporary.

You can see all the selected architects here

These are noble aspirations, and the manifesto helps to keep everything together. I think that Farrell and McNamara have curated a Biennale that is in keeping with their manifesto. Of course, the theme must allow enough room for broad interpretation and yet lend itself to specificity. Farrell and McNamara, and the architects, have done this admirably, and one of the great joys of this Biennale is the effort that has gone into the interpretive signage of each of the 71 or exhibitors in the Venice Giardini and the Corderie within the Venetian Arsenale; the impregnable complex of shipyards that was the epicentre of the Venetian Republic’s power. For each exhibitor, Farrell and McNamara provide for the visitor a piece as to why each was chosen and how their work relates to the overall theme. These little blurbs are concise, well written, refer back to the Freespace manifesto and are a pleasure to read.

And it might seem foolhardy to find a stable point in the plethora of approaches selected and presented at this Biennale. Nevertheless, this Biennale evokes Frampton’s 1983 essay, Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance. In it Frampton argued that optimising technologies had delimited the ability of architects to produce significant urban form. The curators, like Frampton, strenuously advocate for the legitimacy of localised architectural cultures and a discourse resistant to processes of universalisation. The work of Critical Regionalism itself was to, “mediate the impact of universal civilisation with elements derived indirectly from the peculiarities of a particular place.” Much of what the curators have selected in this Biennale accord with this sentiment. So much so they awarded Frampton a Golden Lion.

A Computer #FreeSpace Zone

Best of all this is a Biennale that is very much a computer free zone. Yep. Let me just say that again. This is a biennale that is very much a computer free zone. Yes, there are lots of exquisite laser-cut models, there are obviously computer-generated drawings and diagrams. But for many of these architects, their patrons, and ordinary punters this is an exhibition that is about a kind of bottom up-architecture. There is no bombast or hyperbole related to the latest computer technologies to solve all of our problems. By and large, most exhibitors have provided representations of their own work, rather than pursuing dreary conceptual pieces based on abstract ideas. One might ask Farrell and McNamara, if they think computer hyperbole is diametrically opposed to the aspirations of Freespace?

Of course, between these two polarities–the curator’s against a universal society and the absence of in your face computing–there are other pathologies at play that probably cannot be covered in a blog like this.

A schlock free zone

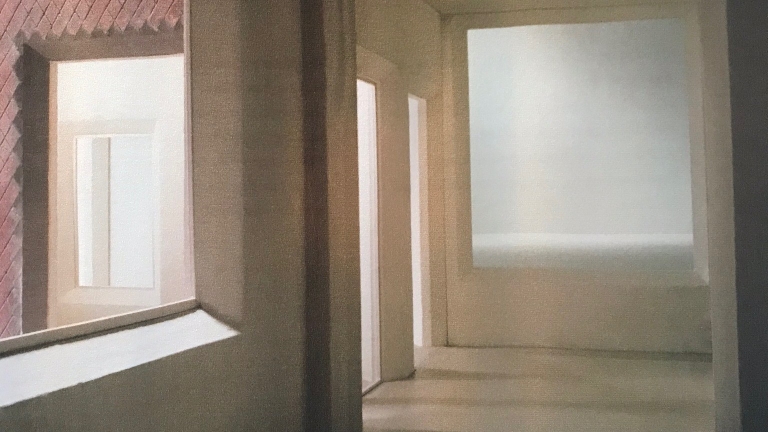

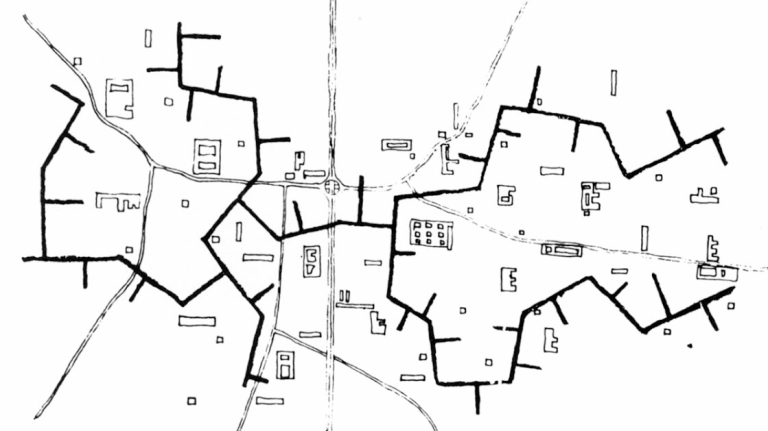

This is a Biennale refreshingly free of abstract schlocky volumes, cheap Eisenman-like syntactics and thankfully para-mucking-metrics. A few installations are overly conceptual, and they fall pretty flat. There is only so much you can do with gauze curtains and multi-media. This is a biennale depicting an architecture still based in the techniques of drawing, model making, section (remember those) and the plan. Yes, the plan, the plan as a working method, before it became an overly coagulated El Lissizky composition; drawn over and over and over again with line sequences adjusted a little bit here and there; lines never expressive enough to break out of the constraints of fluid capital.

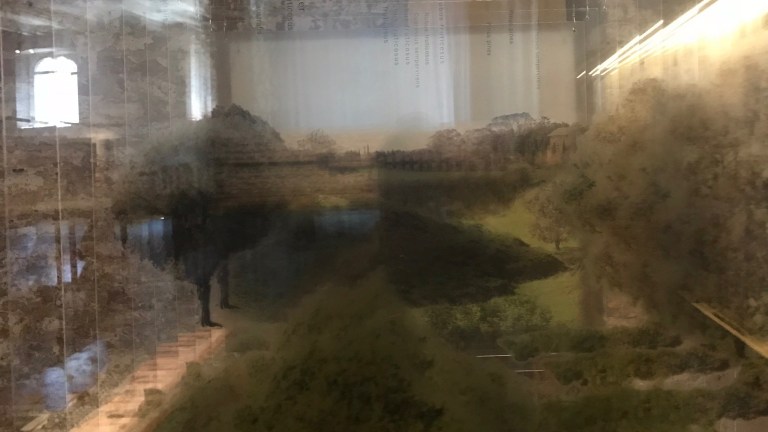

This is a Biennale exhibition of models, materiality, construction and spatial context. An architecture cognisant of regional differences, cultural layers and as the curators say in their manifesto.

FREESPACE encompasses freedom to imagine, the free space of time and memory, binding past, present and future together, building on inherited cultural layers, weaving the archaic with the contemporary.

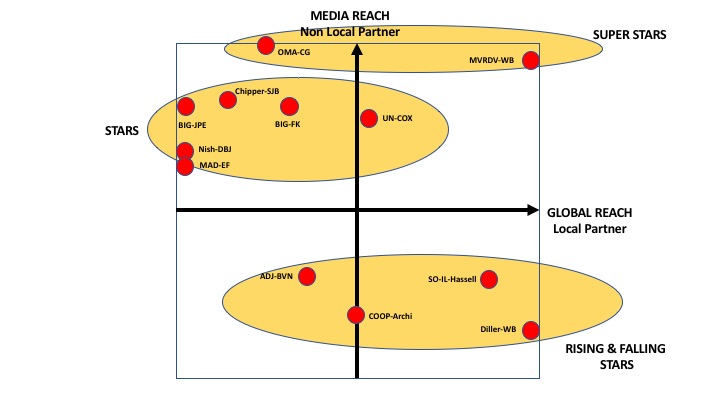

Highlights

This is very much a Biennale that exhibit’s work that is shaped by propositions and experiments of the European city. The stats tend to suggest this: 46 of the firms represented are from Europe, 11 from across Asia, 5 from South America. Peter Rich from South Africa. Notably, the Trumpian republic only has 5. In theory, this Eurocentric focus and pursuit of Frampton’s credo is paradoxically the limitation of this Biennale. In accord with the Freespace manifesto, much of the work of the firms in the Arsenale is focused on exploring layers, community, culture, memory and the morphologies of the European city. Yes, the curators have selected some non-European entries from India, China and South Americas. But overall, the wan light of the iniquitous slum-cities now sprawling across the globe are missing at this Biennale. This is arguably an architecture formed in a Eurocentric bubble, and one wonders if Freespace is radical or confrontational enough to fill the gap. Perhaps in the future, some historians will decide that Betsky’s 2008 Biennale was the last gasp of American architecture.

Nonetheless, the result is refreshing as this is by and large it’s a star architect, and parametric free zone, although beautiful, charming and talkative Bjarke is there with a dreary flooded scheme of New York replete, in a room with plasma screens which have a cheesy blue bubble water that rising up on each screen. It reminded me of the Bubblecup franchise (I guess that’s what happens when you leave Europe and go to New York). Nothing like converting global warming and rising sea levels, to a graphics device on a plasma screen to help avert the actual horrors of climate justice.

Ozzie, Ozzie, Ozzie

And of course what about the Ozzie’s? What about the Ozzie, Ozzie, Ozzie, Oi, Oi, Oi architects. Well, there are two plucky little Australian firms selected by the curators in the Asrsenale. John Wardle and Room 11. Wardle makes it into the Arsenale with a giant kind of conceptual spotted gum (if that was the species) piece, sadly let down by an overwrought plastic red thing with a mirror at the end. I can’t even begin to tell you what it reminds me of. It would have been better to see some of the practice’s work. As for Room 11, from Tasmania, I think I have written about them elsewhere.

Caccia Dominioni

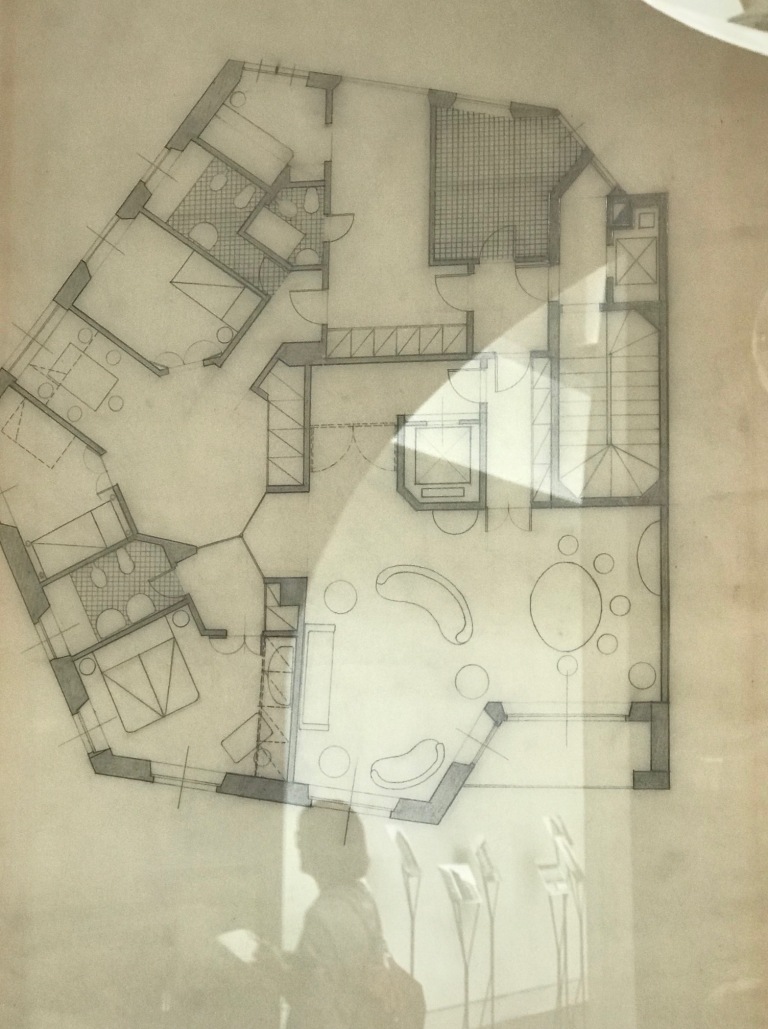

One of the revelations for me was the presentation of the work of the late Milanese architect Caccia Dominioni curated by Cino Zucchi. Dominioni worked to create magnificent apartments for the Milanese bourgeois.

When I see this work I think it indicates a rigorous working method committed to a project that inscribes the lives and habits of a people into the plan. His work is a far cry from the Jim Jims and melamine soaked interiors, featurist luxuries, and cheap scrims in the apartment plans of Australian cities.

In coming weeks I will discuss the Sean Godsell’s contribution at the Holy See, Repair the Australian Pavilion and maybe even the MADA wall. In the meantime don’t forget to help Architeam fund the RASP project.

8. Without wanting to sound like one of those awful American Architecture school

8. Without wanting to sound like one of those awful American Architecture school